The Taro Leaf as a Metaphor for the Rohingya Experience

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

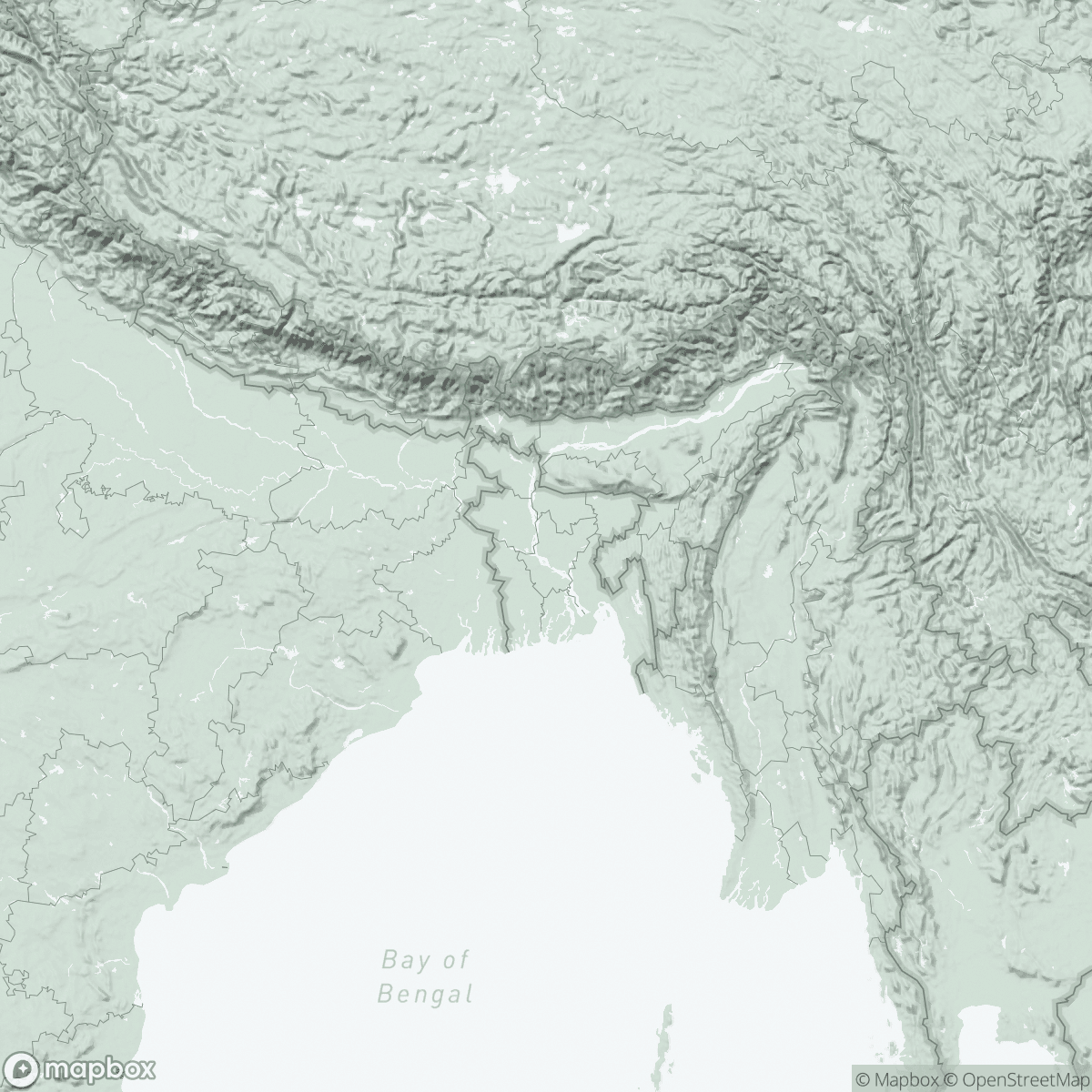

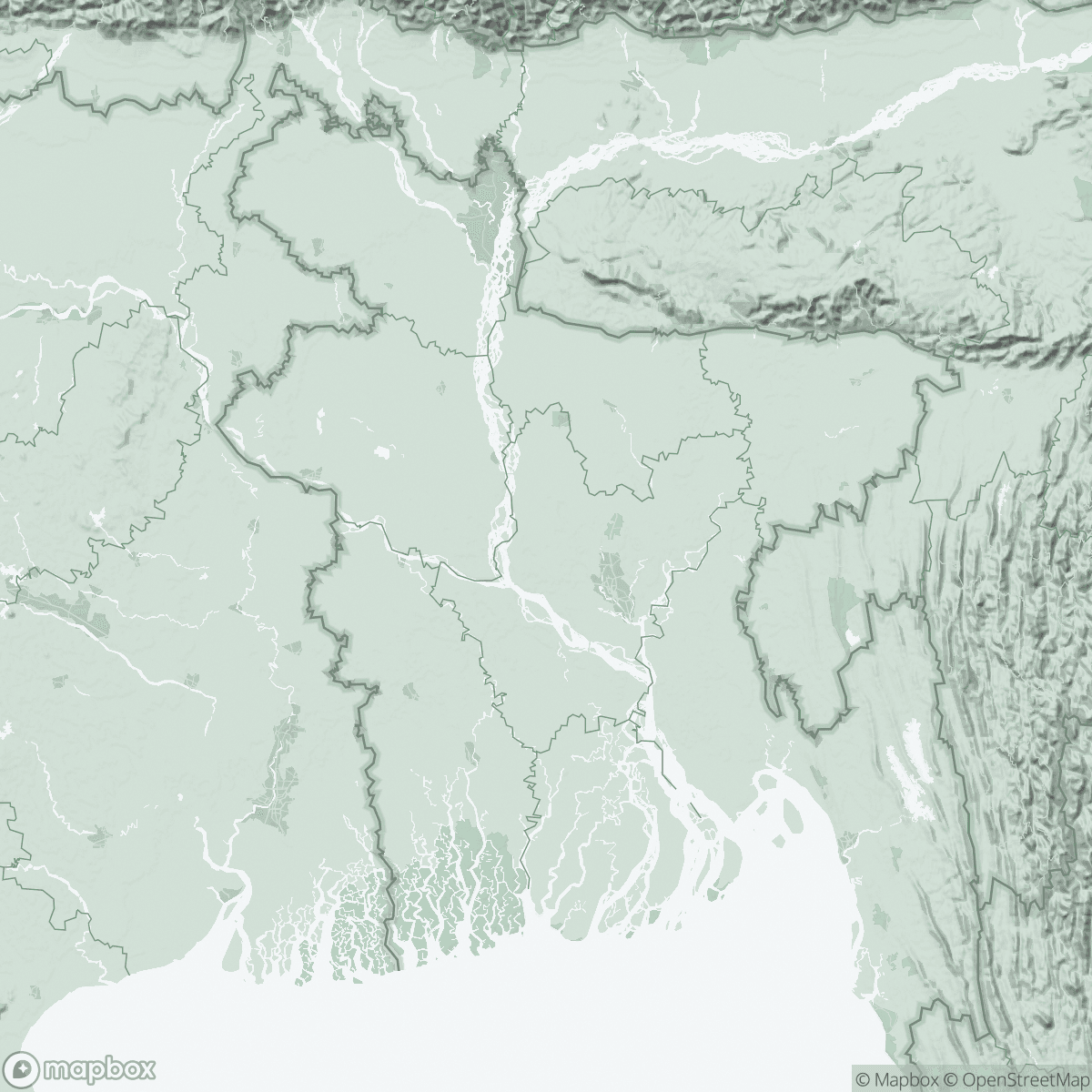

Ruhul Amin and Arunn Jegan met eight years ago in Bangladesh, as more than 700,000 Rohingya arrived in the country fleeing a targeted campaign of extreme violence at the hands of Myanmar’s military. For nearly a decade they have worked together collaborating on projects that challenge the boundaries of what it means to provide care. Here, they discuss their creative partnership and ongoing friendship. They are colleagues at Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF).

Interview :

Arunn: When I met Ruhul, he and his family had just crossed the border into Bangladesh with only the clothes on their backs. I didn’t know him, but he told me he worked for MSF in Myanmar, so I felt a connection. It was heartbreaking to hear how he lost everything. I pointed him to the office where he could collect his salary, he told me he needed water, and we went our separate ways.

Ruhul: When I met Arunn, I didn’t see him properly. I saw a dark-skinned man who said he lived in Australia. I didn’t remember his name or know he was Tamil, a community which also faced atrocities. My mind was focused on survival. Where would we sleep? How would we eat? I was completely exhausted. I felt like I was floating in an ocean, not sure where I could go. I thought I would go home, but little did I know that eight years later I still wouldn’t be able to return to my homeland.

This momentary exchange was the beginning of an enduring partnership. Ruhul and Arunn worked together through emergency responses and longstanding humanitarian programs. But they kept coming back to one question: what does it mean to provide care. Medical care will always be essential, but surviving isn’t the same as living. And the Rohingya struggle to do both.

Ruhul: In 2017, MSF was one of the first NGOs to start working in the new camps that were created following the mass exodus of Rohingya from Myanmar. Within two weeks, we built up a network of community health workers. We had a simple job: take sick people to the hospital and tell people where to find medical aid. People were arriving with gunshot wounds, knife cuts, and untreated infections. There were no toilets, shelters, or roads. I remember three women lying unconscious in the mud, flies all over them. I paid community members 600 taka (about $6 US) from my own pocket to get them to the MSF hospital. We only had human ambulances—people carrying the sick on makeshift bamboo stretchers or their backs.

Arunn: It was raw. It reminded me of my own community’s displacement: Hundreds of thousands of families carrying whatever they could; scores of people with gunshot wounds; the smell of smoke still fresh on their clothes; and families desperate to find their children after being separated in the chaos. We were building hospitals in six weeks, water pumps in days. There was little time to stop and feel anything.

Ruhul: I remember feeling something. When I saw Arunn again years later, I realized what it was: the power of relationships building over time.

As years passed, the needs shifted.

Gunshot wounds sustained in Myanmar became chronic medical conditions. Large epidemics of diphtheria, scabies, and hepatitis C started to menace the community, uncontrollably and rapidly. The Rohingya community faced new challenges that came with life as a refugee.

Infrastructure improved but hopes for the future dimmed. The COVID-19 pandemic and containment policies brought movement restrictions, a barbed-wire fence, and shrinking aid.

The camp, which now hosts over 1.3 million Rohingya refugees—some for decades, others just months—has become a bamboo and tarpaulin slum. Babies are born and people grow old, in limbo.

Ruhul and Arunn now found themselves asking:

What sustains a person when funding disappears? When a person’s legal status hasn’t changed in 40 years? What does it truly mean to be stateless — and what does that mean for those who stand alongside them?"

Arunn: I met Ruhul again in 2019. That’s when I felt like our connection grew. He once told me that it took four years before he felt safe enough to tell me what it really meant to be stateless.

Ruhul: I didn’t call it statelessness. I just called it life. I didn’t expect education. I didn’t think we were allowed to get medical care. I didn’t expect freedom of movement. I thought education and opportunities were only for some people. Our imagination for what our lives could be was very narrow. Only when we left our homeland did we understand how deeply we had been denied our rights. That realization is painful. It doesn’t just hurt your body. It hurts your mind.

From this conversation an idea was born.

If medical aid is meant to heal the body, then what heals the part of us that wonders if we matter?

They set out to create a project rooted in people’s existence, culture, and stories, to help Rohingya people express themselves, resist erasure, and stay connected to who they are. They found Australian and Rohingya artists whose work and mind-set were rooted in these principals, and together they all formed the Creative Advocacy Partnership (CAP).

Ruhul: "A symbol began to emerge in our workshops: the taro leaf."

Inspired by a Rohingya Proverb “Honsu-fathar Phani”, which says that water doesn’t leave a mark on the taro leaf.

Arunn: The surface of a taro leaf is waxy, causing water to bead and roll off without leaving a trace.

Ruhul: It is symbolic of how the world makes Rohingya stateless and tries to leave no mark of us. But we are still here. And we leave a mark.

Arunn: Rohingya adults, children and artists made their own taro leaves. Watching people transform through creativity was profound. A Rohingya ceramicist told us his home was destroyed eight years ago, but he only fled recently. The weight of that slow erasure is unbearable. And yet, in this shared space, people began to open up. Even the tensions between religious and ethnic identities began to soften. That’s the power of creating together.

Ruhul: But it’s not just about expressing ourselves. It’s about survival. NGOs will leave. Funding will dry up. We don’t want to rely on NGOs for the rest of our lives; we bear shame being dependent on others. But if we stay connected to our culture, our identity, our relationships — they can survive as well. Relationships are the most important medicine.

Arunn: "Ruhul told me he feels like the light inside him is dimming. Not because he’s given up, but because the weight of disconnection—from movement, from care, from opportunity—is getting heavier. I am hearing the word “destiny” and “fate” a lot more than “hope” and “future”."

Ruhul: I am not alone—many in the camps feel this. For us this project is not a side activity; it’s a way of keeping the light alive. We still face massive health challenges, with food rations being cut, unexplained fevers, and poor living conditions.. The USAID and UK funding cuts are crippling our future—scores of healthcare centres have shut down. Even my son needed urgent care, and no one would cover the surgery.

Arunn: This isn’t about replacing medical aid with creative advocacy. It’s about recognizing that without both, what is left of a people quickly becomes unrecognisable. Holistic care acknowledges the human need for recognition, connection, and belonging—not just clean bandages or nutrition rations. That’s where humanitarian work must go next.

Ruhul: In a place where people are denied nationality, movement, even medical care, the simple act of shaping clay, weaving bamboo, or telling a story becomes an act of resistance and dignity.

It says: We are still here. We still feel. We still matter.

More information: