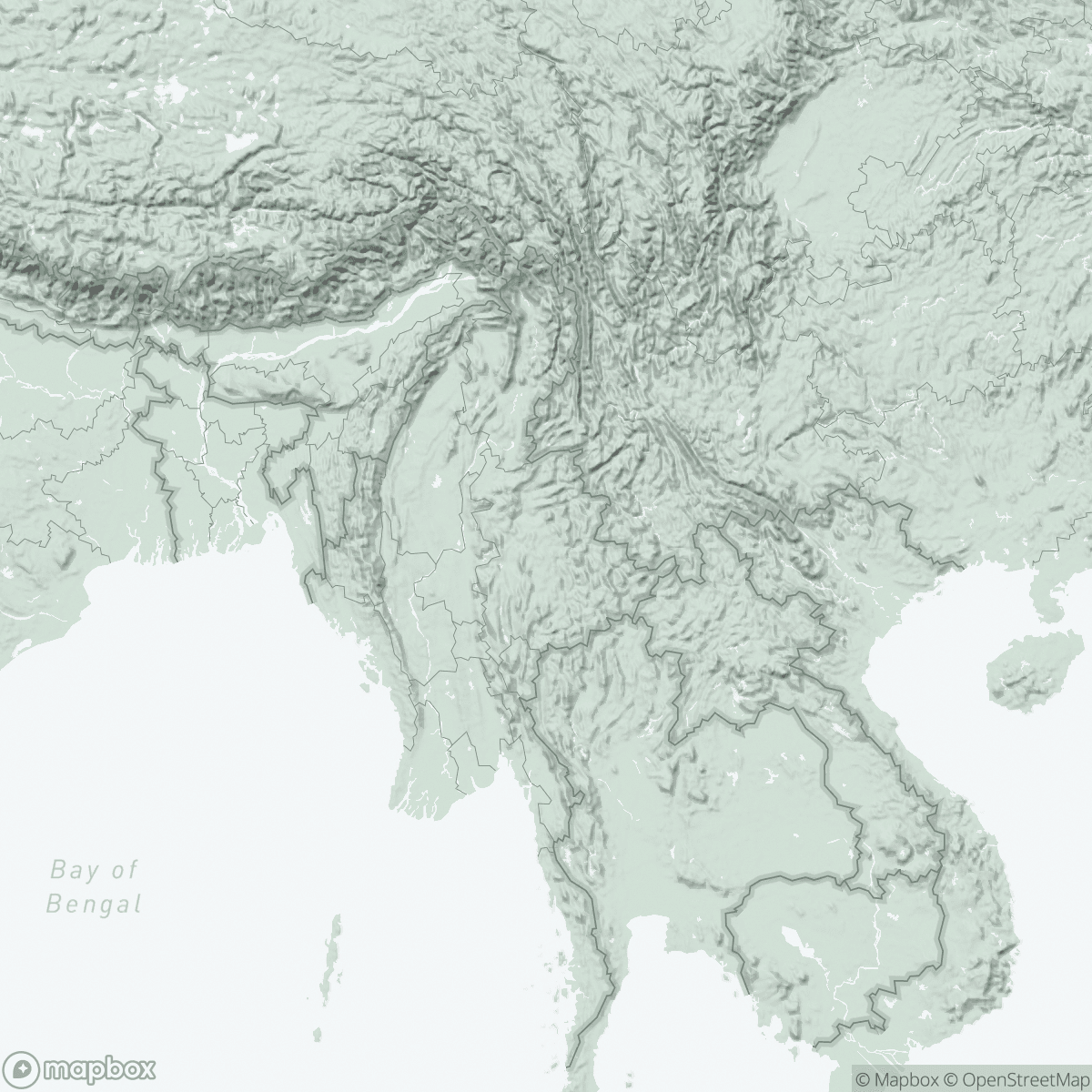

Myanmar

Earthquake in Myanmar: MSF is adapting its emergency response

On March 28, 2025, a 7.7-magnitude earthquake struck central Myanmar, near Mandalay, as well as Thailand.

MSF teams are about to deploy to the affected area. We are deeply concerned about the fate of those impacted. The Sagaing region has been the hardest hit, an area already scarred by years of violence. Six regions are currently in a state of emergency, and the government has made a rare appeal for international aid.

We are doing everything in our power to provide life-saving assistance as quickly as possible. Having worked in the country for 32 years, we expect to be on the ground in a short time. These are the critical moments for the countless people trapped under the rubble. Thanks to the support of our donors, life-saving aid is on its way.

The emergency fund enables MSF to respond swiftly to immediate needs in crisis situations, such as the earthquake in Myanmar.

Our activities in 2024 —

outpatient consultations

antenatal consultations

people started on treatment for TB, including 6 for MDR-TB

people treated for sexual violence

Despite violent attacks on our facilities and movement restrictions for our staff, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) continues to work in Myanmar to assist people affected by widespread violence and recurrent extreme weather events.

Monsoon flooding and typhoon Yagi displaced over 3.5 million people in 2024, adding to the severe suffering already faced by communities since the military seized power from the elected government in 2021.

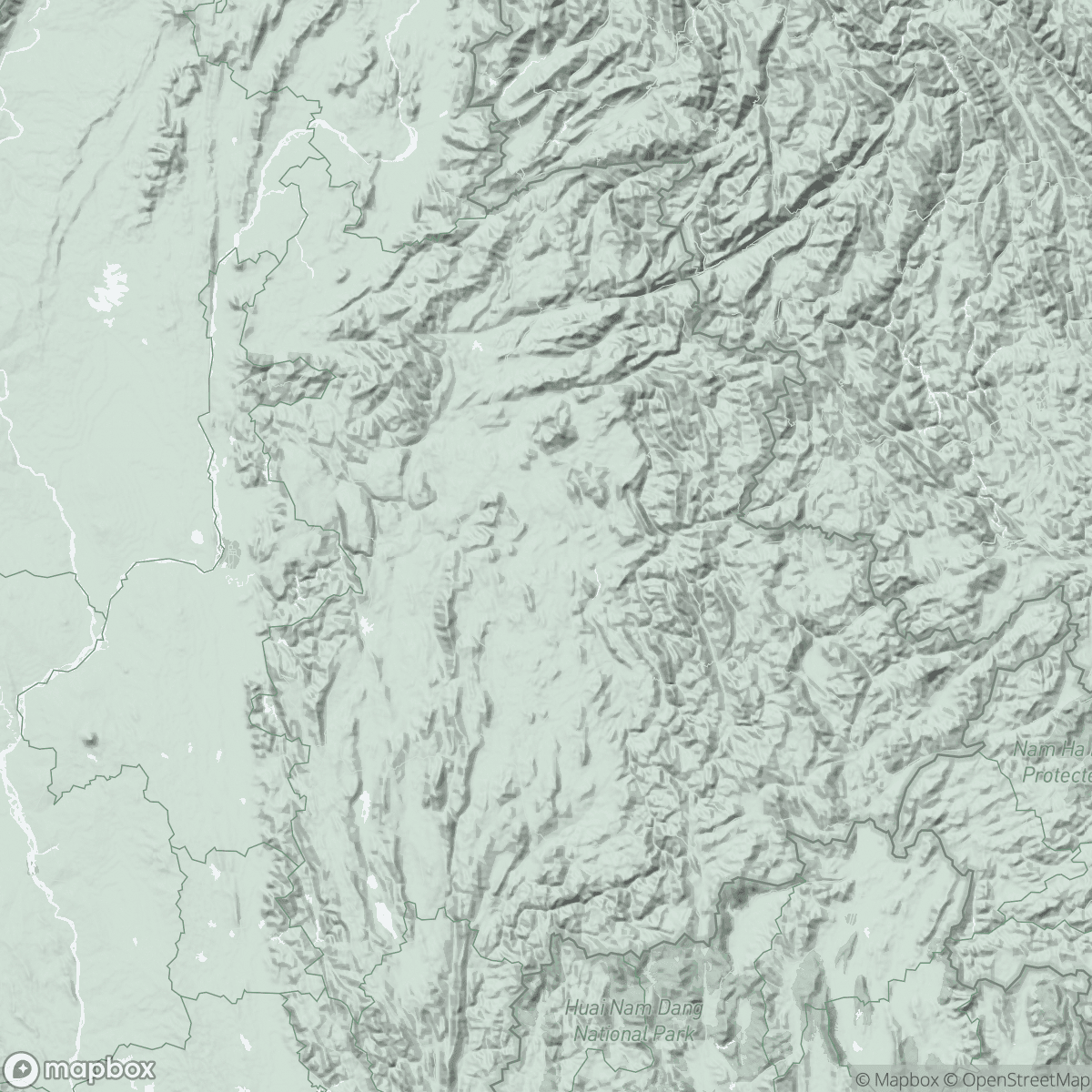

In June, fighting intensified between the Myanmar armed forces and various ethnic and resistance groups, severely affecting MSF’s ability to provide services across Rakhine, Shan, and Kachin states.

In northern Rakhine, we had to indefinitely suspend activities at 14 clinics across Rathedaung, Buthidaung and Maungdaw townships in June. This followed an earlier suspension in April, when our office and pharmacy in Buthidaung were destroyed during horrific violence. For many local communities, these clinics were their only accessible healthcare options.

In eastern Rakhine, we were unable to run previously authorised mobile services due to the authorities’ refusal to issue travel permits. This meant we had to resort to alternative strategies, such as teleconsultations and office-based clinics.

In northern Shan, we were forced to suspend our activities in Lashio and Muse townships, where we had focused on sexual and reproductive health and paediatric care, though we resumed services in Muse in October.

In Kachin, while escalating violence forced us to suspend activities in Bhamo, we continued to address the critical health needs of people in Myitkyina, Hpakant, Mogaung, and Mohnyin, by supporting the national HIV and tuberculosis (TB) programmes. We also provided care for victims and survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive healthcare for pregnant women and lactating mothers, and general healthcare for children under five.

In Yangon, we maintained our support to Aung San TB hospital, and started to offer hepatitis C screening and treatment, and hepatitis B vaccinations.

In Tanintharyi region, in addition to HIV care, we ran general health services, including treatment for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, and sexual and reproductive healthcare. In 2024, we expanded these services to cover Kawthaung, Myanmar’s southernmost district.