“I was sick, not a criminal” : South Sudan’s Mental Health Crisis

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

“I knew I was unwell, but not a criminal. I needed support, not punishment. What hurt the most was that my own family chose prison for me instead of treatment,” recalls thirty-three-year-old Samat Nyuk, a patient recovering from a mental health disorder in Malakal, South Sudan.

Samat was sent to prison by his family when traditional herbs and remedies failed to calm the turmoil in his mind. At the onset of his illness, he experienced vivid and terrifying illusions.

“I felt like I was crossing a river where the water reached my neck, and I saw fingers pointing at me while voices urged me to drown,” he shares.

A friend, noticing Samat’s distress, sought traditional remedies. A local elder gave him n herbal root that brought a momentary reprieve. Concerned for both his son’s safety and their family’s well-being, Samat’s father, Nyuk, asked the local authorities to detain his son or find him help. Samat was restrained in June 2025 and taken to Malakal Central Prison, where he was placed in a small cell in the prison’s isolated section for those suffering from mental illness.

In Malakal, where no psychiatric care is available, families are often left with no alternative — sending their loved ones to jail becomes a desperate last resort.

Life in prison was brutal. Initially, he was confined to a dark cell with nothing but a thin mat. He endured nights of cold, swarms of mosquitoes, and relentless voices in his head.

A Growing but Overlooked Crisis

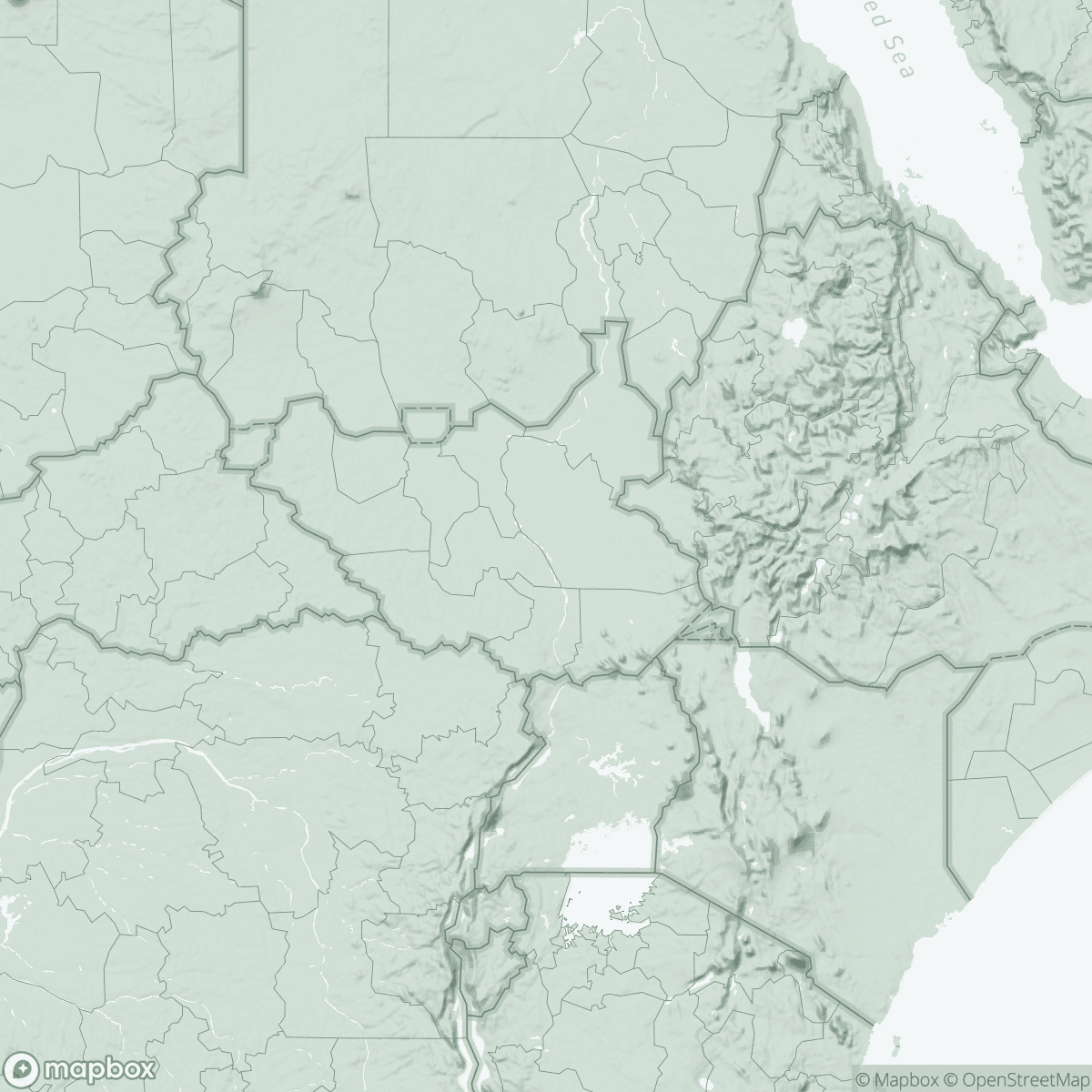

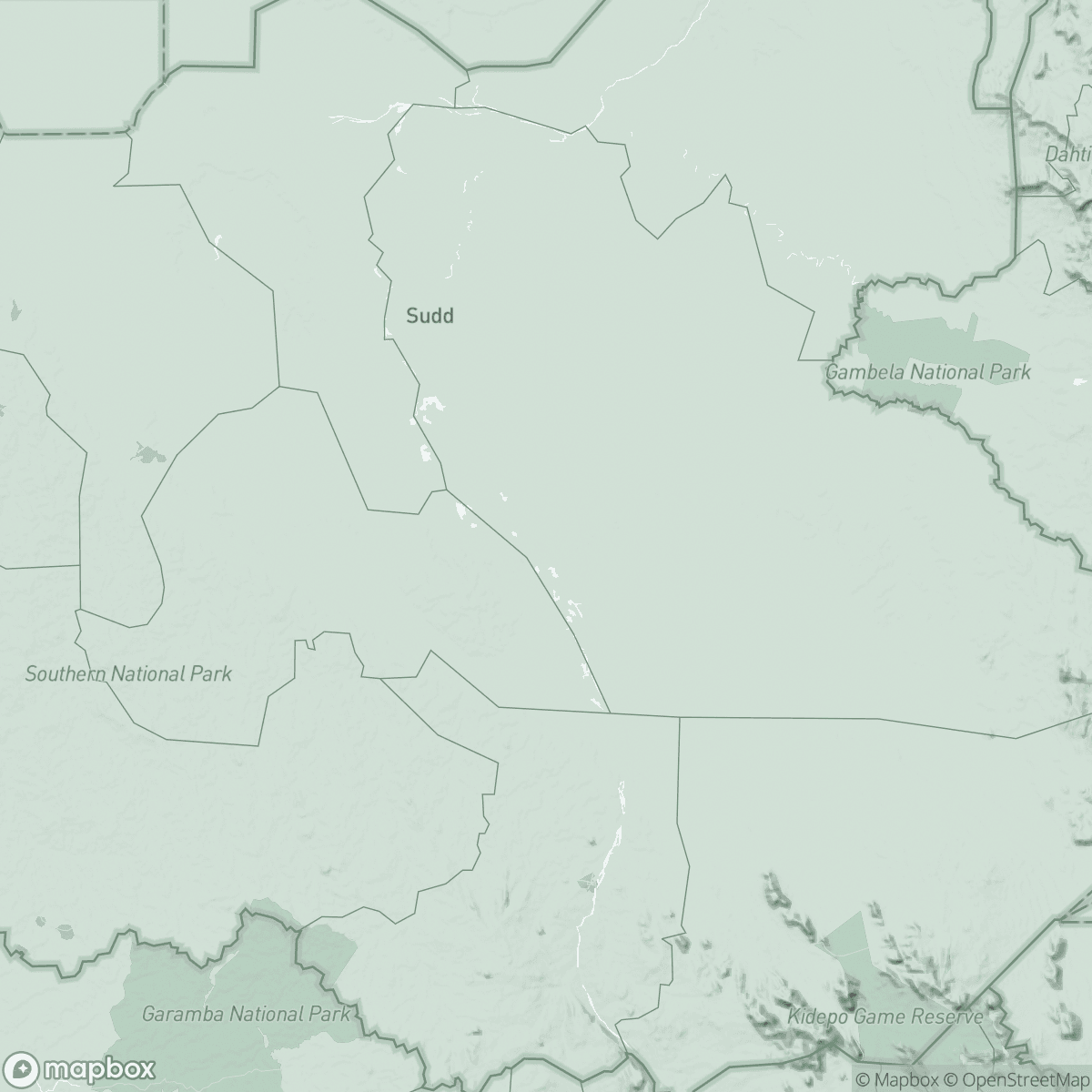

South Sudan is grappling with a profound but often invisible mental health crisis. Decades of conflict, displacement, poverty, and food insecurity have inflicted lasting wounds. Ongoing insecurity and recurrent displacement continue to disrupt essential services, forcing communities to remain on the move and putting health staff and facilities at constant risk. This situation not only deepens the need for mental health support but also severely undermines the ability to deliver sustained care.

Many people live with anxiety, depression, trauma, and post-traumatic stress; however, services remain woefully inadequate. Access to trained professionals, effective treatments, and community awareness is limited.

The outcome is grim: individuals with mental health disorders often face stigma, neglect, or are treated as criminals, leading to their incarceration. Survivors of sexual and gender-based violence face additional layers of trauma, underscoring the need for integrated mental health, protection, and legal support services. These comprehensive responses are resource-intensive and often unavailable in many parts of the country.

On the other hand, mental health and psychosocial support programs remain chronically underfunded and vulnerable to sudden cuts, threatening the continuity of services, staff retention, and the steady supply of essential medicines.

“In many cases, detention centres become the only places where those with severe symptoms can receive care or be kept safe,” says Laura Ximena, MSF’s Mental Health Activity Manager in Malakal. “While this is far from ideal, it reflects the urgent need for enhanced mental health infrastructure in the region.”

In Malakal, MSF provides mental health services at the Malakal Teaching Hospital, and inside the protection of civilians (PoC) site before the closure of the facility in June. Since 2023, MSF has been providing mental health care and psychiatric medications at the Malakal Central Prison. MSF staff members and one staff from the health ministry provide follow-up care through counselling and psychopharmacological treatment. In the detention centre, MSF tries to ensure that patients are doing well and take their medication every day.

Between January and August 2025, MSF provided mental health consultations to 1,130 individuals in Malakal, which includes 761 women (67%) and 369 men (33%).

MSF services primarily supported individuals with various mental health needs. for patients requiring specialized care and pharmacological care, the most common diagnoses include diagnosed with psychosis, bipolar disorder, depression, and mental health comorbidities involving psychoactive substance use.

Samat’s experience mirrors the plight of many patients in need of mental healthcare in South Sudan—faced with limited options, individuals often resort to desperate measures. Some have even held suicidal thoughts. Between January and September this year, 12 patients seen by MSF admitted to contemplating suicide, primarily due to prolonged trauma, instability, inadequate psychosocial support, food insecurity, and exposure to violence. April 2025 saw the highest number of cases, with four patients having attempted suicide and one holding thoughts of suicide.

MSF also conducts awareness sessions in various settings targeting healthcare staff and patients in hospitals. These include brief talks in waiting areas and community focus group discussions with local leaders to promote mutual support and reduce stigma. MSF also holds participatory awareness sessions in secondary schools and runs radio programs conveying messages in local languages.

MSF’s work in Malakal continues to show that with appropriate medication, counselling, and consistent follow-up, as well as family and community support, recovery is possible. However, progress remains fragile without food security, social support, and an effective health system.

“Mental health must be integrated into primary healthcare across South Sudan, ensuring trained professionals are available at all care levels. This also requires securing essential psychotropic medicines, maintaining buffer stocks, and integrating them into existing supply chains,” Ximena asserts.

“Community awareness and family involvement are equally vital. Above all, individuals with mental health conditions deserve to be treated as persons with dignity, and not resort to detention centres where they can be associated with criminals.”

MSF continues to follow up with Samat and other patients sent home, providing them with medication and counselling. Today, Samat is regaining his strength and searching for a job. “What gives me hope now is freedom,” he says. “Prisons are not suitable for individuals with mental health conditions. We need hospitals—places offering treatment, food, and hope for recovery.”