In 1 click, help us spread this information :

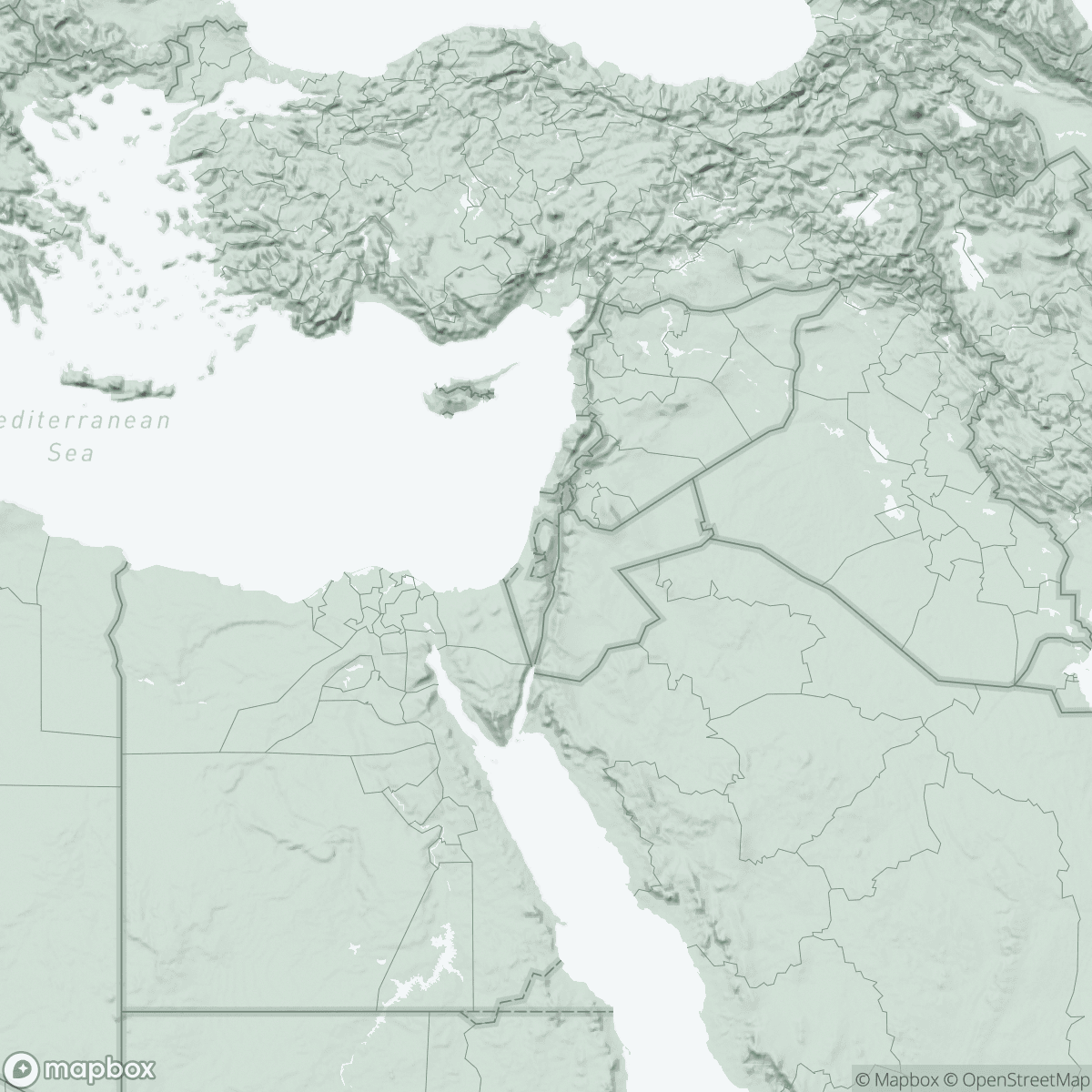

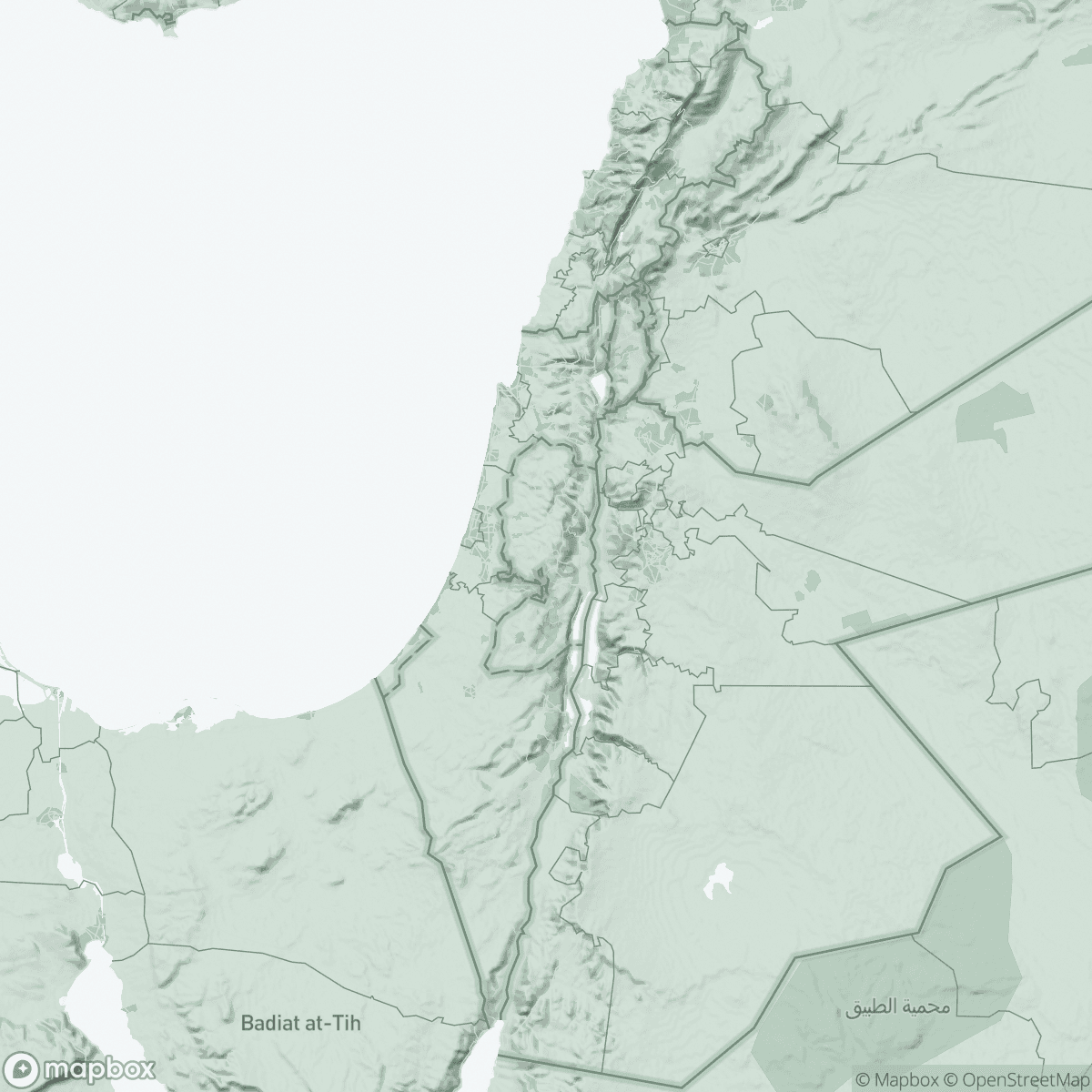

Military incursions by Israeli forces in the West Bank are increasing in violence and frequency since the beginning of the war in Gaza in October 2023. Medical and paramedical staff are repeatedly attacked, harassed, blocked and hindered as they attempt to care for the wounded. Between May 21-23, 2024, Jenin City and its refugee camp endured a 42-hour military incursion, one of the latest and longest in a pattern of brutal raids.

Here is the powerful testimony of Itta Helland-Hansen, MSF project coordinator, who describes the situation in Jenin and Tulkarem, where MSF teams are witnessing a pattern of violence and incursions by Israeli forces, ongoing attacks on healthcare and recurrent obstruction of ambulances.

This incursion started at 8 AM, while children were arriving at school and people were on their way to work.

One of the first victims was Dr Jabarin, a surgeon who was shot in the back and killed while walking to work at Khalil Suleiman Hospital.

He arrived on a stretcher instead, and his colleagues had to carry the extra burden of his loss throughout the incursion. In total, Israeli forces killed twelve Palestinians during this raid.

Incursions in Jenin are becoming more frequent, and they are highly unpredictable, lasting from hours to days. They are primarily focused on Jenin Camp, which houses over 23,000 Palestinian refugees. Snipers are deployed around the camp and city. Military forces in large, armored vehicles block the roads and hinder access to ambulances. It can take hours for people to reach the Khalil Suleiman Hospital, which is normally a two-minute walk from the entrance of Jenin Camp. As the road to the hospital might be a death trap, many choose to stay at home with injuries and conditions which they would otherwise seek acute medical care for.

In most MSF projects, we mitigate a gap in healthcare. Here, healthcare is available down the road, but when it is needed the most, it is deliberately made inaccessible. During incursions in Jenin and Tulkarem, we have witnessed a pattern of continued and systematic attacks on healthcare workers and blockages of ambulances.

Every single paramedic I have spoken to has explained situations where they have been personally harassed, physically assaulted and hindered while trying to provide emergency medical care. Several have been threatened, detained, physically assaulted and some even shot at.

In Jenin, we conduct capacity building for doctors and nurses in the emergency department of Khalil Suleiman Hospital. In Tulkarem, we do the same at Thabet Hospital. But as the patients are blocked from reaching the hospitals on time, we also train ambulance workers, as well as medical and paramedical volunteers in the camps. We aim to enable them to keep injured people alive longer. We had to develop a whole new approach to establish measures beyond immediate lifesaving, so that patients might hold onto life until they can safely access adequate care. We have also equipped stabilization points, simple rooms with a couple of beds and essential medical supplies, in the camps of Jenin and Tulkarem. But as these stabilization points have been attacked and vandalized by Israeli forces during their raids, some medical volunteers no longer feel safe working there. Hence, we moved to giving portable medical kits to volunteers.

Additionally, we initiated “stop the bleed” trainings in the camps, teaching non-medical residents how to care for wounds and apply a tourniquet. During these trainings, we have been asked by housewives, matter-of-factly, whether the bullet needs to be removed before applying pressure, or how long an arm can be tourniqueted before you risk amputation. These questions tell a lot about the alarming reality in Jenin and Tulkarem, where the blockage of access to healthcare has become part of daily life that people are forced to endure.

Incursions also bring massive destruction. Houses are bombed or demolished, streets get torn up, water and sanitation systems are ripped apart, and electricity is cut.

We have donated two tuk-tuks, the size of small golf carts, repurposed to function as mini ambulances inside Jenin Camp.

These lifesaving tuk-tuks run on batteries, therefore volunteers must ration their use as they never know how long a raid might last and when they will be able to charge it again. We cannot add a generator or solar panels to the setup, as this would merely create another target.

Despite constant harassment and fear for their own lives, volunteer paramedics continue to work and tend to the wounded. Mohammed, one of the volunteers in Jenin Camp, told me how he was hit in the wrist by a sniper during the first hour of the latest incursion. He was able to get to the hospital, got patched up, and went right back to work. Some volunteers have expressed that they feel safer when they don’t wear their paramedic vest. What they are facing is a blatant disregard for the medical mission and human life.

We never thought that medical vests were bulletproof, but they should certainly not be targets.

During another recent incursion, in Nur Shams camp in Tulkarem, a Palestinian Red Crescent Society paramedic volunteer trained by MSF was shot in the leg while he was running towards a patient. He was wearing his vest, clearly indicating his medical status. It took more than seven hours before he was allowed to reach the hospital and get the care he needed. Fortunately, he survived. When we asked him if he has a message to the world, he said that he doesn’t, because no one is listening anyway. Here, people feel that they are not seen, not significant, not worthy of attention, and abandoned by the world.

While the funeral of Dr Jabarin was about to take place, I asked Dr Abu Baker, the director of Khalil Suleiman Hospital, what we as MSF could do to help improve their situation. ‘The most important thing you can do’, he said, ‘is let the world know what is happening here.’