Migrant workers in Lebanon: healthcare under the Kafala system

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

In 2020, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) opened a clinic in Beirut providing migrant domestic workers with free-of-charge health consultations and specialist mental health support. Three years later, MSF teams continue to see the impact of the Kafala system on people’s living and working conditions as well as on their physical and mental health.

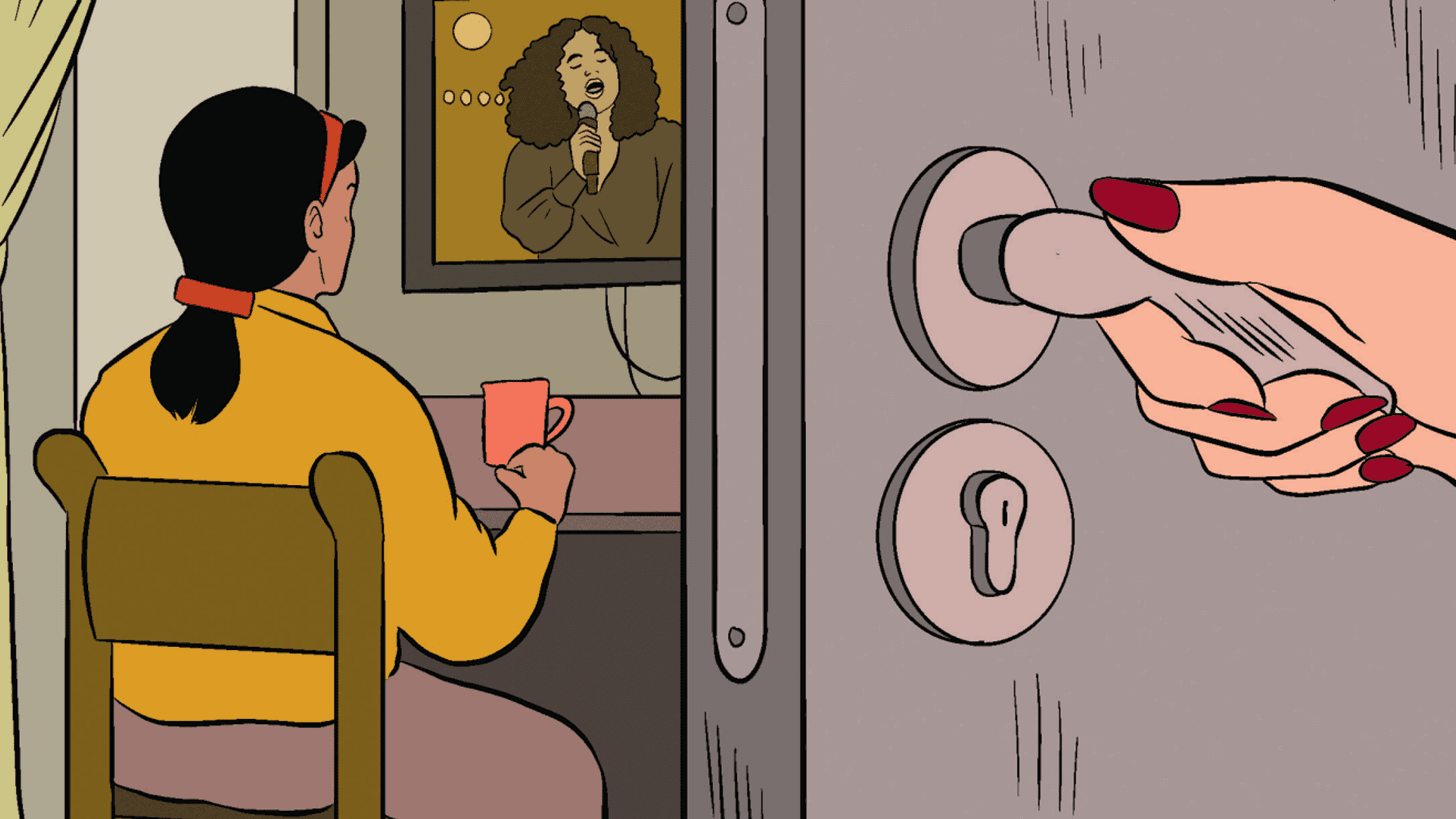

It took a year for Berna [not her real name] to escape her employer. During this period, she worked in a house where she was overworked, isolated, beaten, abused and half-starved. With the help of a neighbour, she managed to flee the house, leaving her passport and belongings behind. She sought medical treatment from MSF and ended up receiving mental health support as well.

According to the latest estimates, there are around 135,000 migrant workers in Lebanon, most from Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka and the Philippines. The majority are women employed in private homes as domestic workers – cleaning, cooking and looking after the children of their employers – under the Kafala system. Under this system, which is the only legal option open to migrant workers in Lebanon, they are sponsored by an employer, who dictates the terms of their contract and the conditions under which they work. This leaves them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, as well as restricting their access to healthcare.

Since 2020, MSF has adopted a multidisciplinary approach towards the increased needs of migrant workers in Lebanon. In Beirut, our team provides general medical consultations, prescriptions and dispensing of medications, basic wound care and minor surgeries, besides referring to partner medical facilities when needed for specialist healthcare.

"Many patients, mostly women, have highlighted the poor and unhealthy conditions in which they live and work, leading to negative impacts in their wellbeing,” says Hanadi Syam, MSF medical referent for the migrant workers project.

In 2022, MSF teams in Lebanon provided 7,686 medical consultations to migrant workers, mostly for patients suffering from musculoskeletal conditions, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory diseases and non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

With rising inflation and transport costs, access to healthcare has become a challenge for many people, often forcing them to prioritise their need for basic essentials, such as food, over healthcare.

In 2023, MSF teams started visiting the neighbourhoods in Beirut and in Mount Lebanon governorates where most migrant domestic workers live, to find people who need healthcare but who cannot easily reach it.

“Most of our patients who do not live in their employers’ houses stay in unsanitary or overcrowded homes, and many turn to destructive behaviours as a coping mechanism,” says MSF psychologist Nour Khoury.

MSF provides psychotherapy and individual counselling, as well as psychiatric care to people with acute mental health needs. In 2022, our team provided 1,471 mental health consultations to migrant domestic workers suffering from depression, trauma, anxiety or psychosis, many of which can be directly linked to their living and working conditions.

Many of our patients have been through difficult life events, whether on their journeys to Lebanon or after they arrived. “They tell us about the difficulties of coping with the socioeconomic crisis and with their daily lives, but also about experiencing violence, forced labour and sometimes even torture,” says Nour.

Engaging with communities and migrant-led associations

Migrant workers in Lebanon come from across Africa and Asia and beyond, and speak a variety of different languages, from Amharic to Sinhala. MSF health promoters engage with the community to help establish relationships with the domestic workers and gain their trust.

“Involving the community of migrant domestic workers is a key component of our approach,” says MSF health promotion manager Dilshad Karaman. “Our aim is to establish transparent and trusting relationships with our patients. By meeting representatives of the community, we are able to listen to their needs and their griefs and to help give them a voice.”

Health promotion teams also provide interpretation services in Amharic, Bengali, French and Sinhala, for patients who do not speak Arabic or English, so that language is not a barrier to their accessing healthcare.

In Lebanon, and especially in Beirut, various migrant-led organisations, such as Egna Legna, support domestic migrant workers by providing legal assistance and financial support and advocating for their rights. MSF teams have participated in capacity-building and awareness trainings run by these community-based organisations, providing training in psychological first aid and sessions on trauma and mental health needs among migrant domestic workers.

The Kafala system

Under the Kafala system, employers – also known as kafeel (sponsors) – are legally bound to provide private health insurance for their domestic workers, but this only includes hospitalisation in case of work-related accidents, and does not include general healthcare, mental health support or the cost of medications. As a result, access to health services is extremely limited for many of the 135,000 migrant workers in Lebanon.

The multi-layered crisis in which Lebanon has been mired since 2019 has further compounded the difficulties experienced by migrant domestic workers, impacting their physical and mental health. Many of those who entered the country legally have since lost their legal status. Often employers could no longer afford to pay their salaries; others fled their employer’s home due to exploitation or violence. Without official documents, it can be much harder to find a job and support themselves, further limiting their ability to access medical care and mental health support.

The COVID-19 lockdown made matters worse, exposing the deep structural flaws of this exploitative system. Many employers stopped paying salaries and some even threw workers out onto the street to fend for themselves or dropped them off in front of their countries’ embassies. This led to rising homelessness and declining living conditions in shared accommodation. Those workers who wanted to be repatriated often found themselves unable to leave Lebanon without the right documents.

“There is an urgent need for reform of the Kafala system,” says Syam. “Efforts should be made to make sure that everyone, irrespective of his or her legal status, is ab le to access healthcare.”