Chad: Water crisis intensifies amid soaring temperatures and shrinking funds

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

Faced with deepening gaps in international aid and rising needs, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is increasingly stepping in to provide life-saving water and sanitation services for hundreds of thousands of refugees and local residents across eastern Chad.

With particularly high temperatures in recent months, the daily search for clean water has become a relentless struggle for most of the 860,000 Sudanese refugees1 and the communities hosting them. Now, with the rainy season fast approaching, the crisis is only set to worsen. Flood risks, water contamination, and overstretched health services loom large. MSF is working closely with Chadian authorities, who shoulder the refugee response and are being hit hardest by shrinking international support.

More than two years of war creating waves of displacement

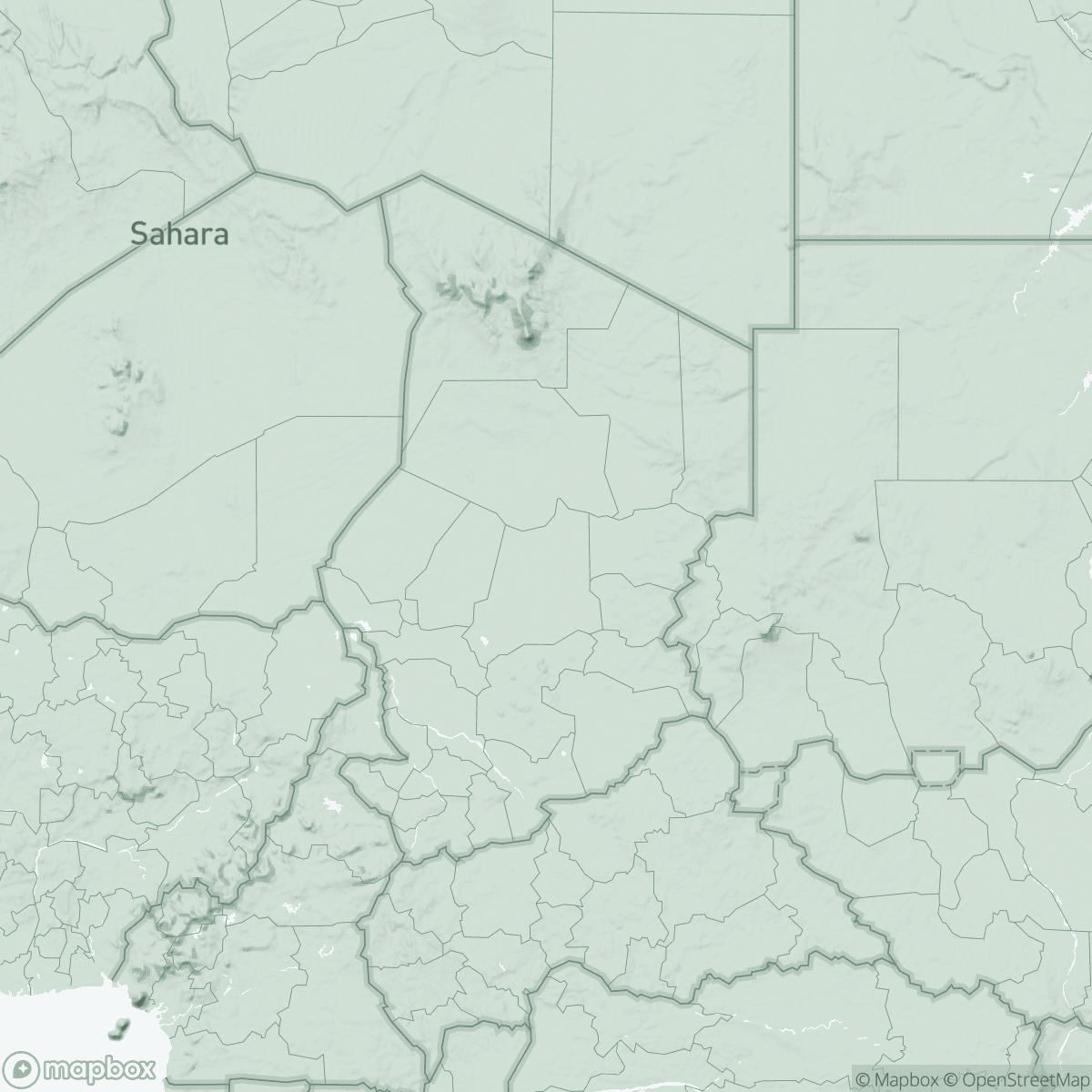

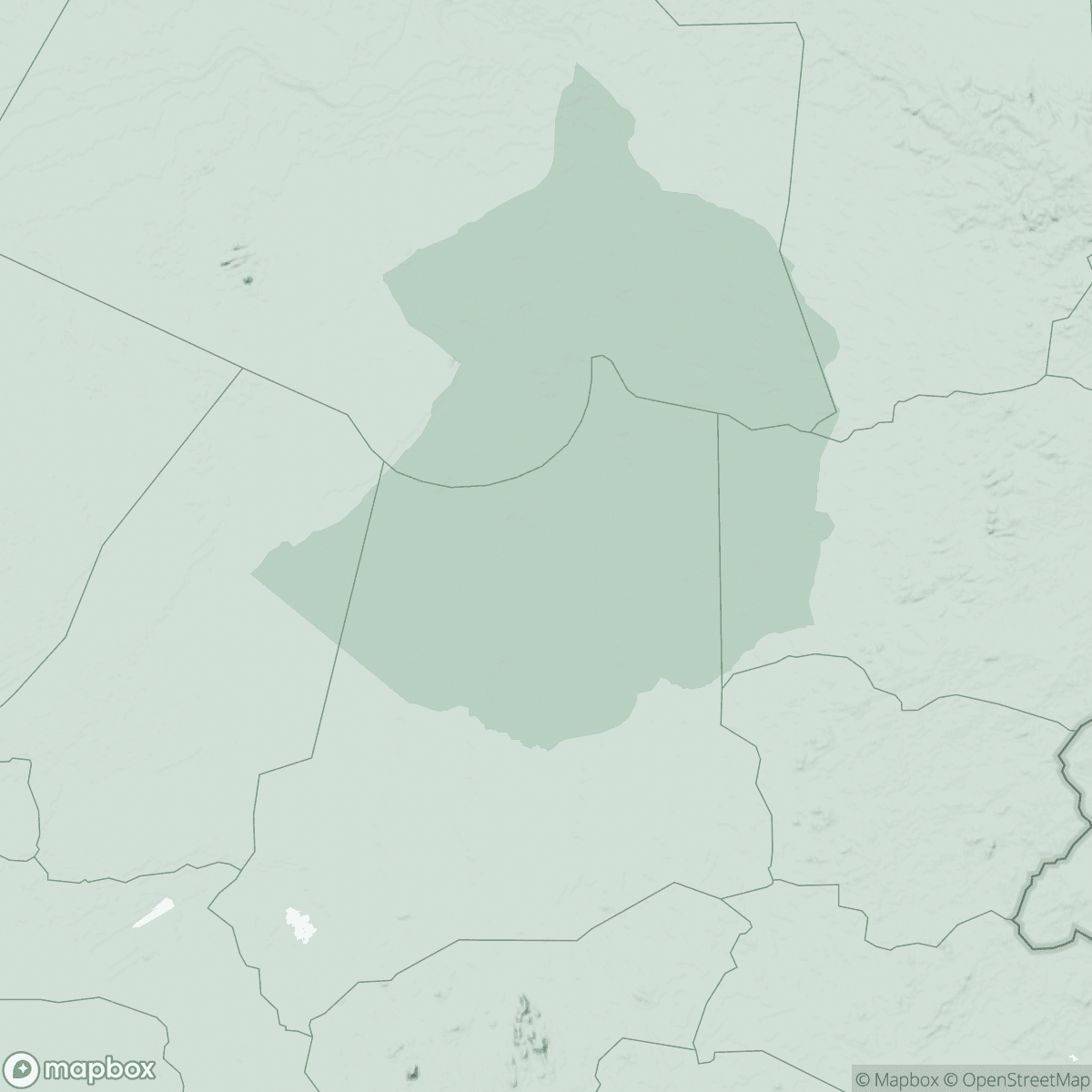

After over two years of war between Sudan’s Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces, tens of thousands of people continue to flee across the border – with more than 85,000 new arrivals in the provinces of Wadi Fira and Ennedi Est since 23 April 2025, according to UNHCR. Each wave of displacement adds pressure to already fragile water and sanitation systems in the camps and surrounding areas.

Providing large-scale water and sanitation in such conditions is both costly and complex. Few humanitarian organizations have the resources to respond, and recent funding cuts are further eroding their capacity. As a result, MSF – already stretched beyond its core medical mandate – is being forced to take on more of the burden.

Not enough clean water, not enough latrines

In refugee camps scattered across Ouaddai, Wadi Fira, and Ennedi Est provinces, most refugees are still receiving far less than the recommended 20 litres of clean water per day. The water crisis is hardest on women and children. With long queues and limited supply, many spend hours each day under the sun to secure water.

I added my three jerrycans to the queue nine days ago. Look here: they still haven’t reached the fountain,” says Leila, a refugee in Metche camp. “I have to keep a constant eye on them – if I don’t move them forward, they get tossed aside. I can’t survive on three jerrycans for my family of nine. I buy extra using my food vouchers,” she says.

There also are not enough latrines, with many camps failing to meet the minimum 1 per 50 people standard. Both poor sanitation and unsafe water increase the risk of skin infections, and the spread of hepatitis E, typhoid, polio and cholera. They can also lead to diarrheal diseases, which prevent the body from absorbing vital nutrients, ultimately causing or worsening malnutrition. In the last two years, MSF treated 43,908 patients for acute malnutrition and responded to hepatitis E and typhoid outbreaks in Adré, Aboutengue and Metche.

“When the rains come, people will start drinking directly from contaminated wadis (or rivers) that people use as latrines,” explains Yasmina, a woman leader for zone 3 in Metche camp. “The danger of disease spreading will increase.”

MSF major provider of water and sanitation amid increasing needs

Since the onset of the crisis, MSF has been a major provider of clean water in three refugee camps in the Ouaddai region – in Adré, Aboutengue and Metche.

In Aboutengue and Metche, MSF initially installed emergency water systems, which were later handed over to partner organizations. Since then, the water supply in Aboutengue has dropped from an average of 12 to 9 litres per person per day. This decline is partly due to geological challenges – boreholes in some areas do not reach deep enough to produce enough water to meet the growing demand.

With water needs still unmet for the 46,000 Sudanese refugees in Aboutengue2 – and 5,000 more people expected to be relocated to the camp soon – MSF is working with partners to upgrade the water system by installing an additional solar-powered network.

In Adré transit camp, MSF-built water systems produced 654,000 litres of water per day in May alone. Since March, one of the 10 boreholes has been extracting water using a solar-powered pump. MSF is investing in solar-powered boreholes with the goal of making them self-sufficient and sustainable for the community.

“This water infrastructure, soon to be handed over to another actor, improves resource management and sustainability by connecting both refugee and host communities to the same water system, strengthening local resilience,” says Toussaint Kouadio, MSF’s Water and Sanitation Coordinator.

Ahead of the rainy season – when the risk of waterborne diseases linked to flooding peaks – MSF rehabilitated 229 latrines in Adré and built 80 new ones designed for long-term use. In collaboration with other actors, 539 latrines have also been emptied. To treat all the wastewater from the camp’s latrines, MSF is setting up a new fecal sludge management plant, similar to the one it built in Aboutengue. This permanent infrastructure aims to create sustainable sanitation services for the entire town, as well as potential opportunities for the local economy. To curb disease and improve hygiene, MSF has also distributed soap and jerrycans in Aboutengue camp. It handed out over 26,000 jerrycans in the first week of July alone, along with 400g of soap per person each month.

In Metche, where 41,000 refugees still do not have enough water, no other actor has stepped in to improve the infrastructure. As a result, MSF is preparing a new water network to support both refugees and the host community.

As thousands of Sudanese refugees arrive to the north in the arid Wadi Fira province, where clean water is extremely limited, MSF has built 50 emergency latrines and distributed 60,000 liters of water daily at Tine transit camp, in addition to providing basic health care services. As relocations continue from transit to refugee camps – already lacking adequate water and sanitation – pressure on scarce resources will only increase.

Mounting needs amid climate emergency, mass displacement, and aid cuts

Chad is vulnerable to recurrent cycles of drought and flooding made more extreme by the climate crisis. This year’s forecast of heavy rainfall has raised urgent concerns, with the government and its partners currently considering a national contingency plan.

Meanwhile, Chad’s refugee situation is unfolding against a backdrop of shrinking global funding. In early 2025, the United States cut nearly all foreign aid, followed by reductions from several European countries. UN agencies such as UNHCR and UNICEF – key actors in water and sanitation – are facing budget shortfalls.

The budget reductions faced by other organizations capable of implementing large-scale water services are limiting their ability to respond, placing an increasing burden on MSF to fill the gap.

We’re taking action because clean water and sanitation are vital – especially with the rainy season approaching,” says Toussaint. “But every penny spent here is one less for medical care. MSF can’t do it alone: we need others with the capacity and funding to step in to meet the growing needs,” he says.