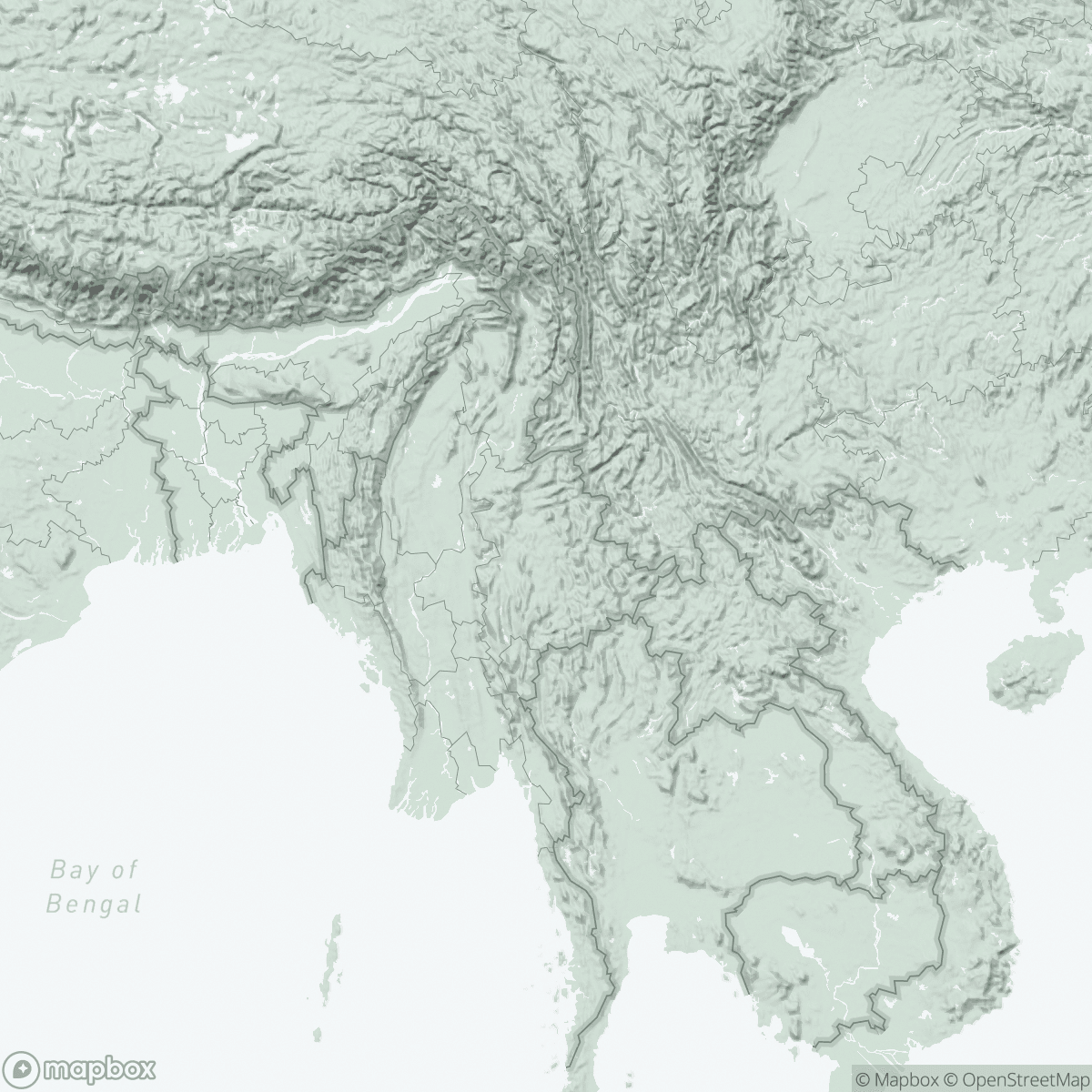

Community Health Workers struggle to respond amid severe restrictions in Rakhine state

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

A new wave of fighting has gripped Myanmar over the past two months. MSF is providing medical humanitarian assistance in Shan, Kachin and Rakhine states, and we have witnessed healthcare facilities damaged or abandoned and hundreds of thousands of newly displaced people attempting to flee for safety.

On 13th November the conflict reignited in Rakhine state, breaking a year-long informal ceasefire. Since then, severe movement restrictions are preventing MSF from running any of the 25 mobile clinics that deliver around 1,500 patient consultations a week.

For the past nine weeks, despite our attempts to find solutions to these blockages, such as providing tele-consultations between patients and doctors, MSF’s community health workers (CHWs) are some of the only people with direct access to our patients.

Community health workers provide vital care

Ann Thar Clinic in Min Bya supports over 4,000 internally displaced people from both Rakhine and Rohingya communities, MSF teams have been unable to run the clinic since 13th November. On 17th November, Min Bya General Hospital, a hospital that MSF uses for emergency referrals came under fire.

Violent attacks and mass displacement

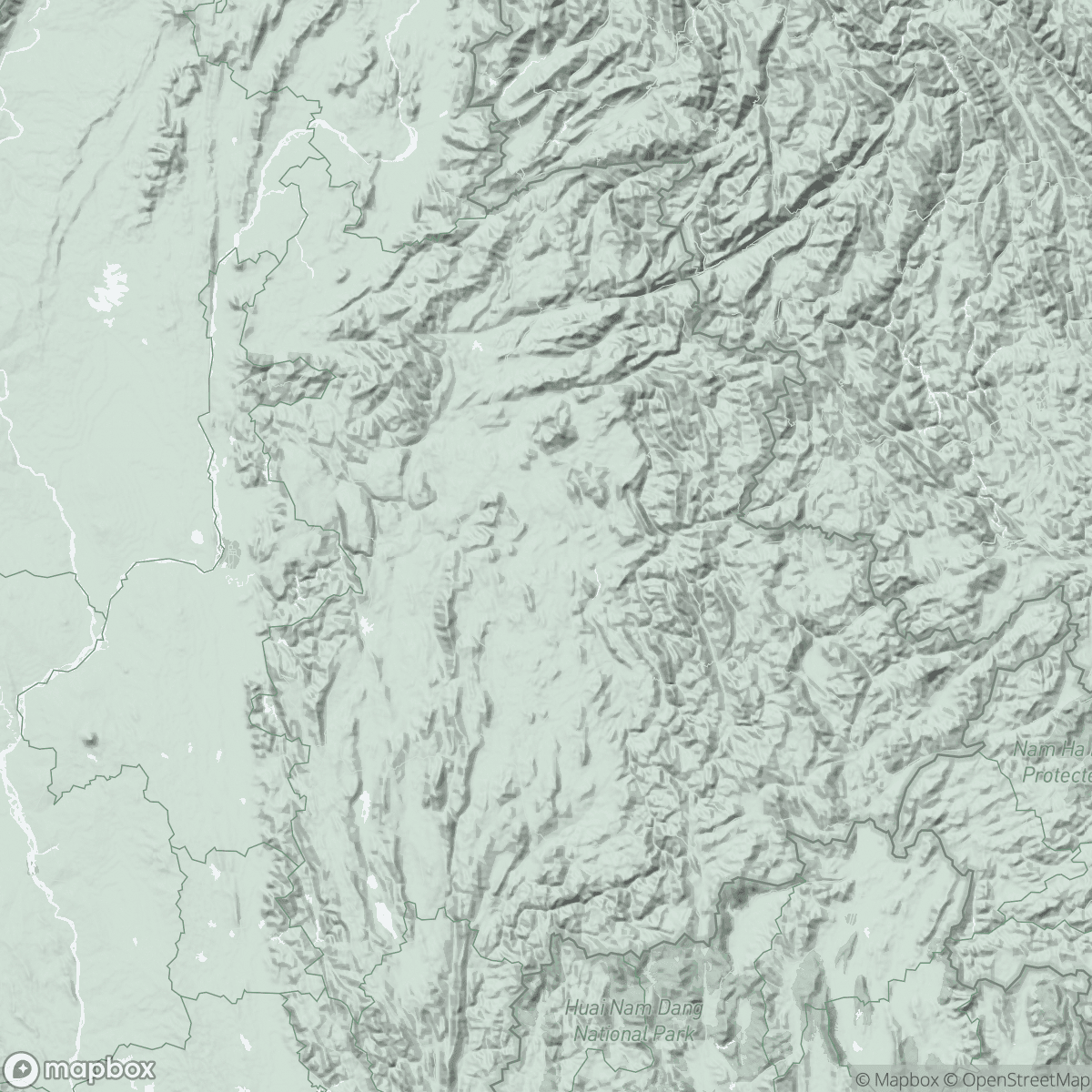

Min Thu is a community health worker in Kyein Ni Pyin camp for displaced people in the Pauktaw area of Rakhine state. Kyein Ni Pyin camp is home to over 7,500 people, most of whom are Rohingya who have been displaced since 2012.

Pauktaw has been one of the most severely impacted townships of Rakhine state, confronted by heavy attacks and mass displacement. The Pauktaw hospital was forced to close and movements in and out of Pauktaw, including to the camps, are practically impossible.

MSF and other organisations are facing serious obstacles to provide any form of assistance, and transport of patients in need of life-saving emergency care is increasingly challenging.

The constant threat of conflict

In Rathedaung, there are many Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps very close to the town, where mostly ethnic Rakhine people who have been displaced since 2019 due to past conflict are living. When recent fighting broke out in the area, the people in these camps fled into more rural areas for safety including MSF’s CHWs.

Unprecedented violence in Myanmar

The level of violence across Myanmar in the last few months is unprecedented and is severely impacting people living in and around the fighting areas where life-saving services are either non-functional or limited and dangerous to reach.

In Rakhine state, communities are already heavily reliant on humanitarian assistance and live with imposed restrictions that limit their freedom of movement. Assistance that was permitted in the state before the conflict was lifesaving, especially for communities in many of the rural areas which our mobile clinics were serving, and who otherwise have no other affordable options for medical care.

Access for humanitarian organisations into Rakhine state has always been meticulously controlled, but the continuation of these current blockages will have a catastrophic impact on people’s health.

Our community health workers are seeing patients lacking their regular medication and with difficulties speaking to doctors, patients being blocked from accessing secondary healthcare, and not being able to afford to access healthcare services further away. According to the latest data from the Global Camp Coordination and Camp Management cluster there have been over 120,000 newly displaced people in Rakhine since 13th November, and this number shows no sign of slowing down.

Hospitals in central Rakhine have been hit during heavy firing or abandoned by staff forced to flee the area.

Two hospitals in Central Rakhine where MSF teams usually take emergency patients are no longer functioning, while another, Min Bya General Hospital was damaged on 17th November.

In northern Rakhine, some emergency referrals have been possible through the support of our community health workers. Health facilities are operating, but some are functioning with only a skeleton staff and limited medical supplies, or else they are shifting their resources into more remote areas to support displaced people moving to and from locations looking for safety.

With access routes blocked and without authorisations to provide assistance, MSF cannot run its 25 mobile clinics. These restrictions are impacting other humanitarian organisations too, with many reporting they cannot deliver their regular interventions.

Parties to the conflict should ensure that healthcare facilities and humanitarian workers can continue to operate and must guarantee safe access to healthcare for the Rakhine population.