Between enemy lines: the destruction of healthcare in Ukraine

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

To date, MSF teams have only been allowed entry into regions controlled by Ukrainian forces, which means they have witnessed the destruction caused by the war in Ukrainian-held territory only. Despite MSF's efforts to obtain permission to access regions under Russian occupation, this access has not been granted; MSF has therefore been unable to observe the situation in areas under Russian military control.

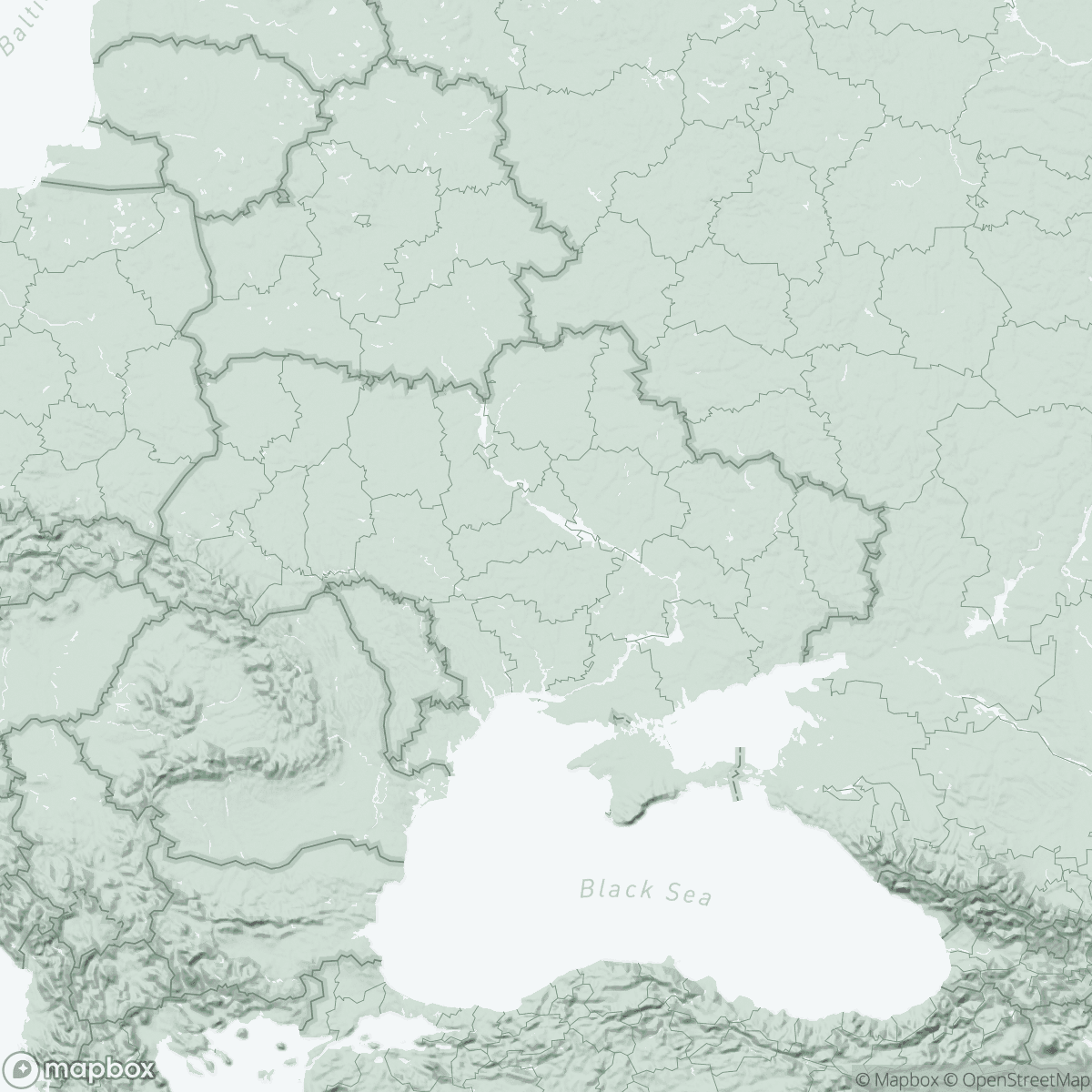

The following information has been collected in areas under attack (Mykolaiv, Apostolove) and areas formerly occupied by Russia and retaken by Ukrainian forces (regions of Donetsk and Kherson). The information is either based on the direct observation of MSF teams or on what MSF patients and local health staff have reported to them. While these accounts provide only a snapshot of the devastation caused by the war, they bear witness to the suffering of the civilian population.

A pattern of devastation

The frontline of the Ukrainian war stretches almost 1,000 km. Before the dramatic escalation of violence in 2022, more than 14,000 people had died in this war1. Since February 2022, thousands more have been killed, wounded or traumatised, while more than 5.3 million have been internally displaced2 and 8.1 million have sought refuge abroad3. In response to the 2022 invasion of Russian forces, the Ukrainian military launched a counter-offensive in August 2022. By 11 November, Ukraine had re-taken 74,443 square km4 previously under Russian occupation.

Since the escalation of the war in February 2022, MSF has scaled up its humanitarian activities in Ukraine, with an emphasis on support for people living near the frontline, where the humanitarian and medical needs are most acute. This support has taken the form of surgical and emergency room care, evacuating patients to medical facilities further from the frontline, providing essential medicines and medical equipment, establishing mobile medical clinics, and providing physiotherapy and mental healthcare.

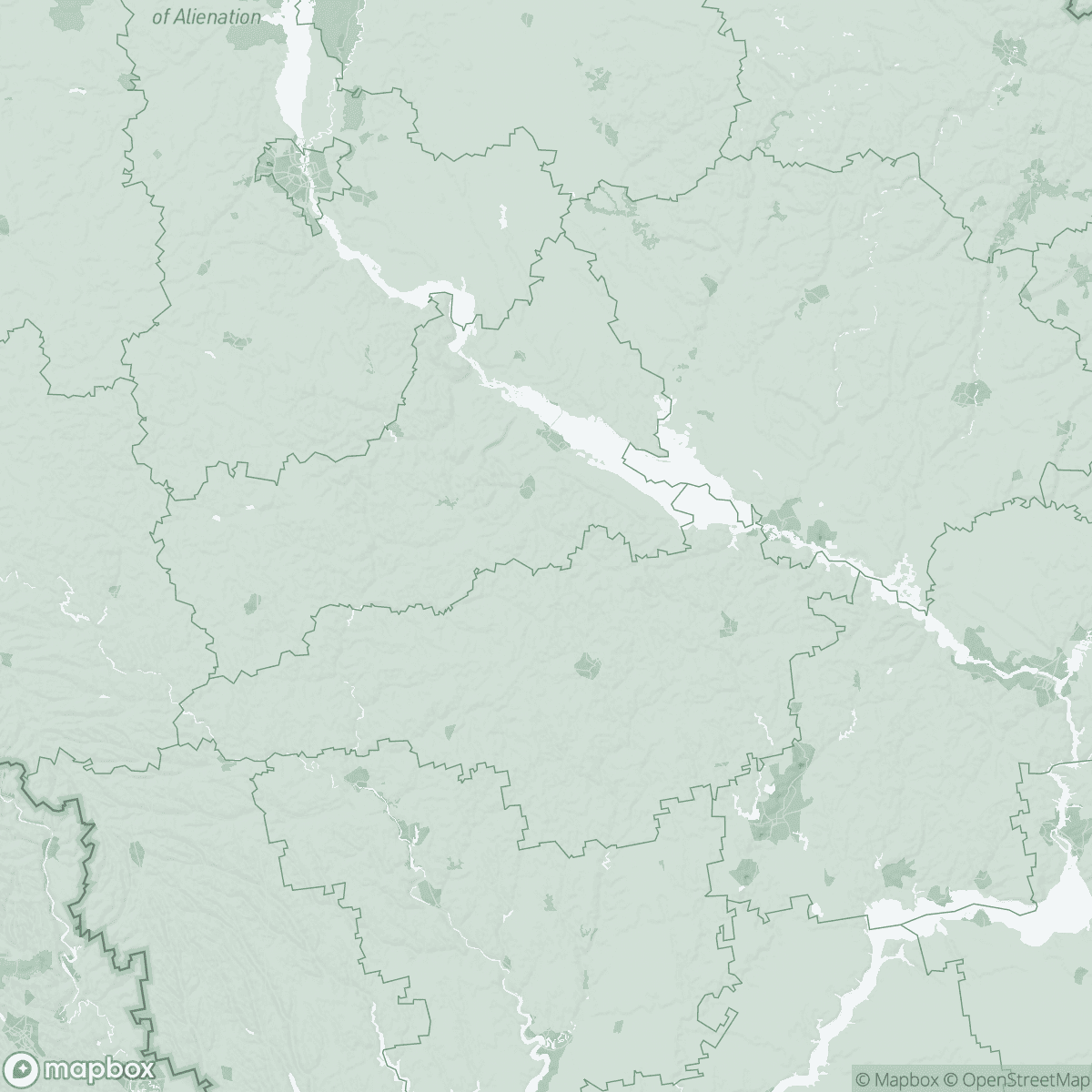

Following the frontline’s shift toward the southeast, MSF teams assessed the medical and humanitarian needs of people in 161 towns and villages that had been caught between shifting frontlines in Donetsk and Kherson regions. The aim was to provide medical treatment for those still living in the contested territory; often the medical teams worked as close as 12 km from the frontline. What they witnessed was a pattern of devastation: homes, shops, playgrounds, schools and hospitals reduced to rubble by incessant shelling and bombing.

Drobysheve, a village in Donetsk region, was one such location. MSF medical teams could not find a single building left with the structural integrity to serve as a makeshift clinic; in the end they repurposed imported shipping containers as clinics. They followed this practice in 10 different villages in Kherson and Donetsk regions.

As with Drobysheve, some of the villages in Kherson and Donetsk regions have undergone two or three changes of control between the two sides, involving heavy fighting. In the battle for villages like Drobysheve, it is very likely that the destruction arose from the use of heavy artillery by both sides, leaving little respite for those caught in the middle.

“In some of the towns and villages where we work, the destruction is absolute. In 25 years of working in warzones, there are perhaps just one or two instances where I’ve seen similar devastation – places like Mosul or Grozny. Along the 1,000 km of frontline in Ukraine, some areas have simply been wiped off the map.” Christopher Stokes, MSF head of programmes in Ukraine

In areas of Kherson region retaken by Ukrainian forces, 89 medical facilities have been damaged beyond functioning5. Based on the towns and villages where these facilities were, and taking into account the number of people who have been displaced, this leaves more than 163,000 people6 with no access to medical facilities.

Attacks on healthcare infrastructure

In early 2022, MSF medical workers were already seeing attacks on healthcare infrastructure using various weapons. On two separate occasions, MSF medical teams witnessed the apparent impact of cluster munitions on hospitals.

On 4 April 2022, a team from MSF visited Mykolaiv town, in southeast Ukraine, to meet with city and regional health authorities. At around 3.30 pm, as the team entered the city’s oncology hospital, which has been treating wounded patients since the end of February 2022, the area around the hospital came under fire from Russian forces. Following several explosions in close proximity to them, the team emerged from their shelter and saw dead and wounded people in the street. Later that day, they witnessed an attack that hit the city’s paediatric hospital. There was no massive crater, as with so many other explosions; instead there were numerous small holes in the building and ground surrounding the area – an impact consistent with the use of cluster munitions7.

On the morning of 15 June 2022, another MSF team witnessed similar damage in Apostolove hospital directorate, in the south of Dnipro region. This was a functioning hospital which had come under fire during the night. Once again there were hundreds of holes in the hospital building and ground, and fragments of shrapnel in the clinic and surrounding area. As a result of this attack, medical activities were suspended by the director of the hospital and MSF medical teams for several days until the area had been decontaminated and confirmed safe, effectively denying patients access to medical care in case of emergency.

Following the Ukrainian counter-offensive, MSF was able to reach numerous medical facilities located in former Russian-occupied areas in both Kherson and Donetsk regions. MSF medical teams discovered that the facilities had been looted, while medical vehicles including ambulances had been destroyed. Inside two of these facilities they saw weapons and explosives.

While the widespread destruction of civilian infrastructure by shelling and airstrikes has been well-documented in this war, MSF also witnessed three separate instances of the presence of anti-personnel landmines inside functioning hospital compounds – on 8, 11 and 15 October 2022. These medical facilities were in areas previously under Russian occupation in Kherson, Donetsk and Izyum regions.

“The use of landmines is widespread in frontline areas, but to see them actually placed in medical facilities is shocking – a remarkable act of inhumanity. It sends a clear message to those who come in search of medicines or treatments: hospitals are not a safe place.” Vincenzo Porpiglia, MSF project coordinator for Donetsk region

A further fatal illustration of the dangers faced by healthcare facilities and providers was exemplified by the shelling of Kherson city’s main square on 16 December 2022, where MSF had previously established a mobile medical clinic, but stopped activities because of the danger of shelling. After MSF’s withdrawal, the Ukrainian Red Cross resumed mobile medical clinics; when the site was hit, two people were killed.

Healthcare under occupation

Between 15 November 2022 and 19 February 2023, MSF’s medical teams provided around 11,000 consultations to people in towns and villages in formerly Russian-occupied areas of Donetsk and Kherson regions. These teams observed that people who had been unable to flee had few options for accessing healthcare. The majority (65 per cent) of patients were older, less mobile or suffering from chronic diseases, including chronic hypertension, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Often these chronic diseases had gone untreated for several months, while food shortages had prevented them from controlling their diets, leading to problems with mobility, eyesight and muscle function, and increasing their dependence on others.

From November 2022 to January 2023, MSF conducted 48 interviews with patients and health practitioners, who described access to essential medicines and medical care being severely restricted during the Russian occupation. This corroborated reports from many more private consultations between MSF staff and patients. According to the patients and health practitioners, those medical facilities and pharmacies that were not destroyed were looted, while the supply of medicines was not assured by the occupying forces.

“Only a few doctors and medical staff remained in the hospital when Russian troops entered our town. We had no surgeons at all. People with shrapnel injuries were brought to the hospital every day. We helped them. Gradually we were running out of medical supplies.

I had to go to the Russians and tell them that we had nothing to treat people with. For example, we did not have urethral catheters, which are needed for people with serious injuries who are being treated in intensive care and cannot get up. We had to soak these catheters in special solutions and then reuse them. We didn't even have urine collection bags and used bottles instead. There was also a pressing need for medicines for people with diabetes and high blood pressure.

Most of the people who stayed behind were elderly and had chronic diseases. (…) Once the Russians told us: ‘Write down the list of medicines, we will give you everything.’ I must have given them those lists 10 times. The list consisted of 86 items and they gave us only 16 – bandages, gauze, plastic bedcovers, cannulas, syringes and a few medications such as painkillers and anti-inflammatory pills. I asked them: ‘How should I treat, for example, hypertension or diabetes?’” Doctor, Kherson region

The difficulties of obtaining medicines and accessing medical care is further corroborated by messages sent by mobile phone between MSF medical teams and Ukrainian doctors and nurses working in Russian-occupied areas of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions who made repeated requests to be supplied with essential medicines.

From May to September 2022, MSF was able to fulfil a limited number of these requests with the support of Ukrainian volunteer organisations, who worked to move essential medicines and supplies from Ukrainian-held territory to areas under Russian military control. The only officially authorised crossing point at the frontline was in Vasylivka, a town in Zaporizhzhia region. However, from September 2022, the flow of supplies entering Russian-occupied areas from Ukraine was impeded, and MSF teams had no option but to stop sending medical supplies.

According to patients’ reports, some people survived for months without essential medicines in areas with fierce fighting; many were visibly weakened by their experiences, which frequently included seeing their villages turned into battlegrounds, relentless shelling and the disappearance and death of family members.

"Several people who approached us during mobile clinics were in pain. They just needed painkillers, which they did not have access to in their village during occupation. They told us they did not see doctors or paramedics during occupation; some people received medicine as humanitarian aid, but they didn't know how to use the medicine.

I treated a man who needed a dressing for his wound, but he didn't have anything for months. He had no disinfectant solutions, no antiseptics, no dressing materials. He just washed and reused the dressing.” MSF doctor, mobile clinic team, Donetsk region

Patients told MSF that their ability to obtain treatment from medical facilities was curtailed by a number of factors, including restrictions on their movements. In several instances, villagers were not allowed to leave their streets for months at a time, even to look for essential medicines.

Because of the destruction of healthcare facilities, people needing emergency care had to travel much longer distances than before, through dangerous terrain, putting themselves at greater risk. A 65-year-old female patient from Borozenske village in Kherson region described how she had to accompany her husband through 12 checkpoints to an emergency medical consultation while the area was under Russian occupation:

“Borozenske outpatient clinic was severely damaged during the occupation. All the computers and equipment were stolen. In May, my husband slipped from a ladder and badly injured his foot. We contacted the doctor who used to work at the clinic, but he couldn’t help us – he didn’t have any more medicines or equipment, so he recommended that we go to Berislav hospital. It’s 50 km away from Borozenske and we needed to cross 12 Russian checkpoints to reach the hospital. We had to get back to Borozenske before the imposed curfew. You can imagine how, faced with these challenges, access to healthcare was not a priority for people unless it was a matter of life or death.” MSF patient, Borozenske village, Kherson region

Although it is difficult to discern a clear pattern, the interviews conducted with MSF patients indicate that the treatment of civilians and their access to healthcare under Russian occupation depended on the unpredictable behaviour of individual Russian units.

Numerous MSF patients described asking occupation authorities for assistance and for medicines, with varying results. Sometimes requests for assistance were flatly refused, even by military doctors; at other times, people were asked to write lists of the medicines required, although these never materialised.

Patients indicated that the behaviour of Russian units varied widely, with some actively working to treat wounded civilians and ensure the provision of medicine, while others looted pharmacies and medical facilities.

Furthermore, medical practitioners who previously lived in areas occupied by Russian forces described to MSF teams the treatment they received at the hands of soldiers, which included intimidation, detention, violence and ill-treatment. One doctor working in a facility currently supported by MSF described his experiences:

“Russian soldiers came to my house to arrest me. They took me to the administrative department, where I was interrogated for two hours. They told me they want the hospital staff to collaborate with them. They beat me. They ordered me to stop speaking Ukrainian.

I was eventually released but the soldiers came back a week later, this time at the hospital. They handcuffed me in front of all the hospital staff. They forced me into a vehicle and took me to the basement of my home where they beat me again. There were at least 10 of them. They destroyed everything in the basement, house and garage.

They kept the keys to my house and took me to the Russian-occupied police station. I was put in a cell in the basement for half an hour before a soldier met me and told me I had a few hours to leave the area or else they would kill me. I was told not to return to the hospital or speak with any of the staff.

They sat me in my car and followed me in the direction of the grey zone. The road was full of landmines. I started driving, terrified that I’d die in my car. I made it across the fields to the Ukrainian armed forces. I showed them the cuts and bruises caused by the handcuffs on my hands, and they helped me cross to controlled territory to reach my family.” Doctor, Mykolaiv region

Conclusion

The level of destruction in the war in Ukraine has been massive, crippling medical infrastructure in the process. This will have a long-term impact on people’s access to healthcare. In interviews conducted by MSF, patients who lived in territories occupied by Russia since the February 2022 invasion reported severe restrictions on their access to essential medicines and medical facilities, as well as the looting of hospitals and pharmacies. Their reports are consistent with the medical condition of many MSF patients, many of whom went without treatment for months.

Warring parties must respect international humanitarian law and abide by their obligations to protect civilians and civilian infrastructure; hospitals and other healthcare facilities must never be targets. Warring parties must allow the unobstructed supply of lifesaving medicines and medical supplies and provide safe and unhindered access to independent humanitarian assistance for those in need.

MSF in Ukraine

MSF first worked in Ukraine in 1999. Since 24 February 2022, we have significantly scaled up and reoriented our activities to respond to the needs created by the war in Ukraine. Today MSF is working in Apostolove, Dnipro, Fastiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Kharkiv, Konstiantynivka, Kropyvnytskyi, Kryyih Rih, Kyiv, Lviv, Lyman, Mykolaiv, Odessa, Pokrovsk, Sloviansk, Ternopil, Uzhhorod Zaporizhzhia and Zhytomyr. Our medical services include emergency surgery, tuberculosis treatment, care for survivors of sexual violence, physiotherapy and mental healthcare. We also run a fleet of ambulances and a specialist medical evacuation train; in 2022, 2,558 patients, including 700 with trauma injuries, were evacuated from near the frontline.