Giving birth without losing one’s life

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

Every two minutes, a woman dies from complications during pregnancy or childbirth. Most of these deaths could be prevented with access to timely and quality obstetric care.

In 2023, approximately 260,000 women worldwide died from pregnancy- and childbirth-related complications, according to United Nations data. This equates to more than 700 deaths per day. The vast majority occurred in low- and middle-income countries, where access to maternal health services remains limited or nonexistent.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) denounces that these deaths are not inevitable and could be prevented with timely and quality obstetric care. The organization also warns that current cuts to humanitarian funding will further worsen this crisis.

The organisation also warns that current cuts to humanitarian funding will further worsen this crisis.

Pregnant women are among the most vulnerable people in contexts of war, forced displacement, extreme violence, or natural disasters.

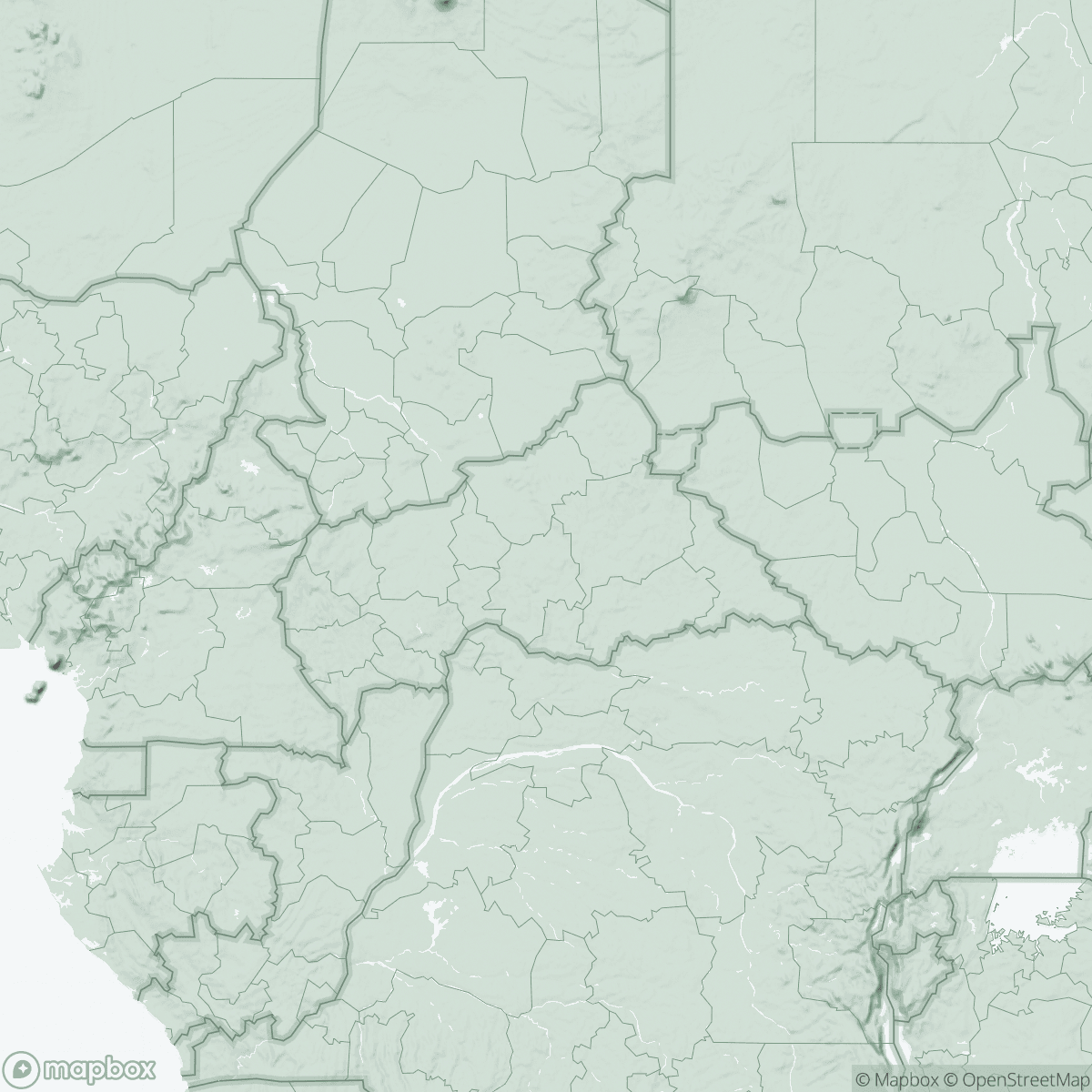

In countries like Nigeria, the Central African Republic, and Bangladesh, where MSF works, the difficulties in accessing life-saving medical care are strikingly similar despite the distance between continents.

Hermina has just given birth at the hospital in Batangafo, in northern Central African Republic.

I walked from five until nine in the morning. I had to come alone,” she explains while cradling her newborn.

In this region, some women travel up to 100 kilometers to receive care during pregnancy or childbirth.

In northern Nigeria, Murjanatu delayed seeking medical care because she could not afford even the most basic prenatal consultations.

If you don’t have money, no one treats you,” she explains from Shinkafi hospital, where she is waiting to be referred for treatment for severe anemia.

In Bangladesh, Sabera, a Rohingya refugee in Cox’s Bazar, says that sometimes the only way to get to the hospital is to sell household items or go into debt.

Some husbands allow their wives to go to the hospital, but others do not,” she adds.

The “Three Delays” that can be deadly

The main causes of maternal death — hemorrhages and infections generally after childbirth, hypertension during pregnancy, complications during labor, and unsafe abortions — are largely preventable. However, many women die due to what is known as the “three delays”: the delay in deciding to seek medical care, the delay in reaching a health facility, and the delay in receiving adequate treatment once there.

The lack of health centers, long distances, insecurity, lack or cost of transportation, and shortages of staff and medicines make it almost impossible for many women to arrive on time,” explains Nadine Karenzi, MSF’s medical coordinator in Batangafo.

In some contexts, health centers operate only a few hours a day or lack qualified staff to handle obstetric emergencies.

These barriers are compounded by social and cultural factors.

A woman may be bleeding or suffering a serious complication, but she is not allowed to go to the hospital without her husband’s permission,” notes Patience Otse, MSF midwife supervisor in Shinkafi.

Stigma, gender inequality, and lack of autonomy further limit women’s ability to make decisions about their own health.

Unsafe abortion remains one of the most overlooked — and stigmatized — causes of maternal mortality in many of the contexts where MSF works.

“We regularly treat women with serious and potentially life-threatening complications following abortions performed in unsanitary conditions,” explains Raquel Vives, midwife and MSF sexual and reproductive health expert.

Restrictive laws, stigma, and lack of access to contraception push women to take extreme risks.”

When it does not result in death, unsafe abortion can cause infertility, chronic pain, and other lifelong consequences. The lack of data and the silence surrounding this reality make the problem largely invisible.

Funding cuts will increase maternal deaths

“When complications arise, speed is everything, but it is not always possible to anticipate them,” emphasizes Vives. “That is why it is essential that women can give birth in health facilities with qualified staff. However, in many places, resources barely cover uncomplicated births.”

Preventing maternal deaths requires long-term investment in prenatal care, qualified healthcare personnel, referral systems, blood banks, and family planning. Yet these essential services remain a low political and financial priority in many contexts.

Current cuts to humanitarian funding threaten to worsen an already existing crisis. “Most maternal deaths could be prevented with timely and adequate care,” Vives insists.

Reducing available resources even further will only increase the number of women and newborns who die from preventable causes.”

Maternal mortality is also a reflection of broader inequalities affecting women’s health and rights. The death of a mother has profound consequences for the family and community beyond the immediate loss of life. Babies whose mothers die are 46 times more likely to die before reaching one month of age and are more likely to suffer malnutrition and miss routine vaccinations.

Every woman who dies leaves her children in a more vulnerable situation and perpetuates the risk for the next generation,” adds Vives.

“Gender inequality remains a key factor limiting access to safe and dignified care.”

In 2024, MSF teams assisted in 369,000 births worldwide — more than 1,000 per day — a 9% increase compared to 2023.

Nigeria, the Central African Republic, and Bangladesh accounted for around 15% of these births. That same year, MSF provided 63,200 safe abortions, a 16% increase from the previous year.

In addition to childbirth care, MSF implements strategies to reduce the “three delays” and other life-threatening barriers for women: maternal waiting homes near hospitals, support for referral systems, emergency transportation, work with community midwives and traditional birth attendants, and community awareness activities.