Tigray Crisis: “We are suffering from a lack of medical care”

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

Most shops are now open in Shire and there is food available in the market, but most people have no money to buy it. The city’s civil servants only recently received their first salary since the fighting started, and even those who have money in the bank cannot access it because most banks are still closed. The price of food and other items has gone up, and many of the displaced people did not bring any money.

MSF carried out a nutritional survey with children under five in the sites and found that while the situation is concerning, it is not at emergency level yet. “What we saw was that the overall global malnutrition rate in the sites was about 11 percent. There was 9% moderate and 2 % severe malnutrition, which is under the emergency threshold. There is food instability and there is definitely a risk for it to become a nutritional crisis. We have to keep a close eye on it,” says MSF medical team leader Juniper Gordon.

All of the food that has been donated so far are bags of wheat and some cooking oil. That means that what most people in the sites eat every day is only bread – which is not nutritious enough, especially for children, pregnant mothers and sick people. 60-year old Demsas* has type 2 diabetes for which he recently received tablets from Shire hospital. “The doctor advised me to eat a variety of food – goat meat, milk, injera - but I can’t afford it. Before, I was a farmer and a butcher and ate well, but when I came here, we just received some wheat.”

Precarious conditions in IDP sites

On Shire’s university campus, hundreds of people are staying in former student dormitory buildings, sleeping in bunk beds. Those who have not found a place in the dormitories stay in an unfinished building on the campus. With bricks placed around their sleeping areas, families are trying to create a resemblance of privacy. Only some people have mattresses or beds, most sleep on the concrete floor. There are no walls to protect them from the cold at night. There is smoke from fireplaces everywhere, and the ever-present sound of people coughing.

In the clinics that MSF has been running in the IDP sites since January, respiratory tract infections are the main morbidity our teams are seeing. Is it COVID-19? Nobody knows for sure. There are no tests available, and there is no way for people to keep a safe distance from each other in the overcrowded sites, no way to buy masks or wash their hands frequently. Compared to the many other issues people are facing, COVID-19 is low on the list of people’s worries.

Diarrhea is the second-biggest medical problem, due to a lack of clean drinking water and sanitation, and unhygienic living conditions. MSF has built latrines in an IDP site in a primary school and carries out regular water trucking. Our teams have also rehabilitated a large toilet and shower building on the University campus. Water supply is not a just an issue in the IDP sites, but the whole of Shire town.

Curfew is a major obstacle for pregnant women

Living conditions are particularly hard on pregnant women. 26-year old Adiam* has fled from a village near Humera and now lives in the University site. She is eight months pregnant with her first child. “Delivering a baby in these circumstances will be difficult, but I am glad I am here with my family. Many other families have been separated. I want to deliver at the hospital but I am worried what will happen if the baby is born at night, after the curfew. I don’t know how to get to the hospital then.”

After 6.30 pm, people cannot leave their homes, and while ambulances are in theory allowed to operate, none are available. Until recently, there was also no staff in the hospital after dark, leaving patients on their own during the night. MSF is giving expecting mothers safe delivery kits in the IDP sites in case they go into labour after dark.

Adonay*, a healthcare professional from Western Tigray who lives in the University site, says he has helped deliver three babies there.“ I delivered them inside the dorms, in the women’s beds. There were many people around. There was no privacy. Fortunately, all deliveries went well. At that time, no health centers were open or staffed. We are several health care providers living in this site, and we have been able to help people before MSF and other organizations arrived.”

Patients with chronic diseases are without medication

Patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes or hypertension face some of the biggest challenges. They have not received any medication for months. “Diabetic patients have not had insulin for three months, which is very dangerous,” says Juniper Gordon. “In the camps, some patients who have TB and HIV also have not had medication for months. Now, the central pharmacy board in Shire is up and running and they are trying to get medication to the facilities. For some medications like insulin that needs a cold chain it is a big challenge – there has not been electricity until the beginning of February in Shire, and it is still not reliable. In the majority of regions outside of Shire there is still no electricity.”

Shire hospital serves a population of more than one million people in the area. After fighting broke out in the city, many staff members did not return to work for a long time, some out of fear for their safety, others out of a lack of motivation because they did not receive any salary. Both staff and patients had no food at the beginning, and when MSF arrived, we supplied the hospital kitchen with food and cleaned the facility as no cleaners had come for weeks. The hospital was not badly looted, but there have been many robberies at night in the past few months because no staff was present. MSF is supporting the pediatric ward, the in-patient therapeutics feeding center as well as water and waste management activities at the hospital.

Birhane* is a 58-year old farmer who is sitting in the waiting area of MSF’s primary health clinic at the University IDP site. With his weathered face, traditional white headscarf and stooped, thin body perched on a walking stick, he looks much older. He says he has walked 2 ½ hours from his village to get medical care. Birhane says that the health center that served his farming community of 2,500 people has been closed since November, and that all six staff have left. “We are suffering from a lack of medical care. We don’t have any medication; the village’s two ambulances were taken. Many people are sick. Three pregnant women have died during childbirth in the past three months,” the farmer says. “There is no food in the village. Our fields have been looted. Some of our women have been raped. We stayed for two months in the forest and we are still scared.”

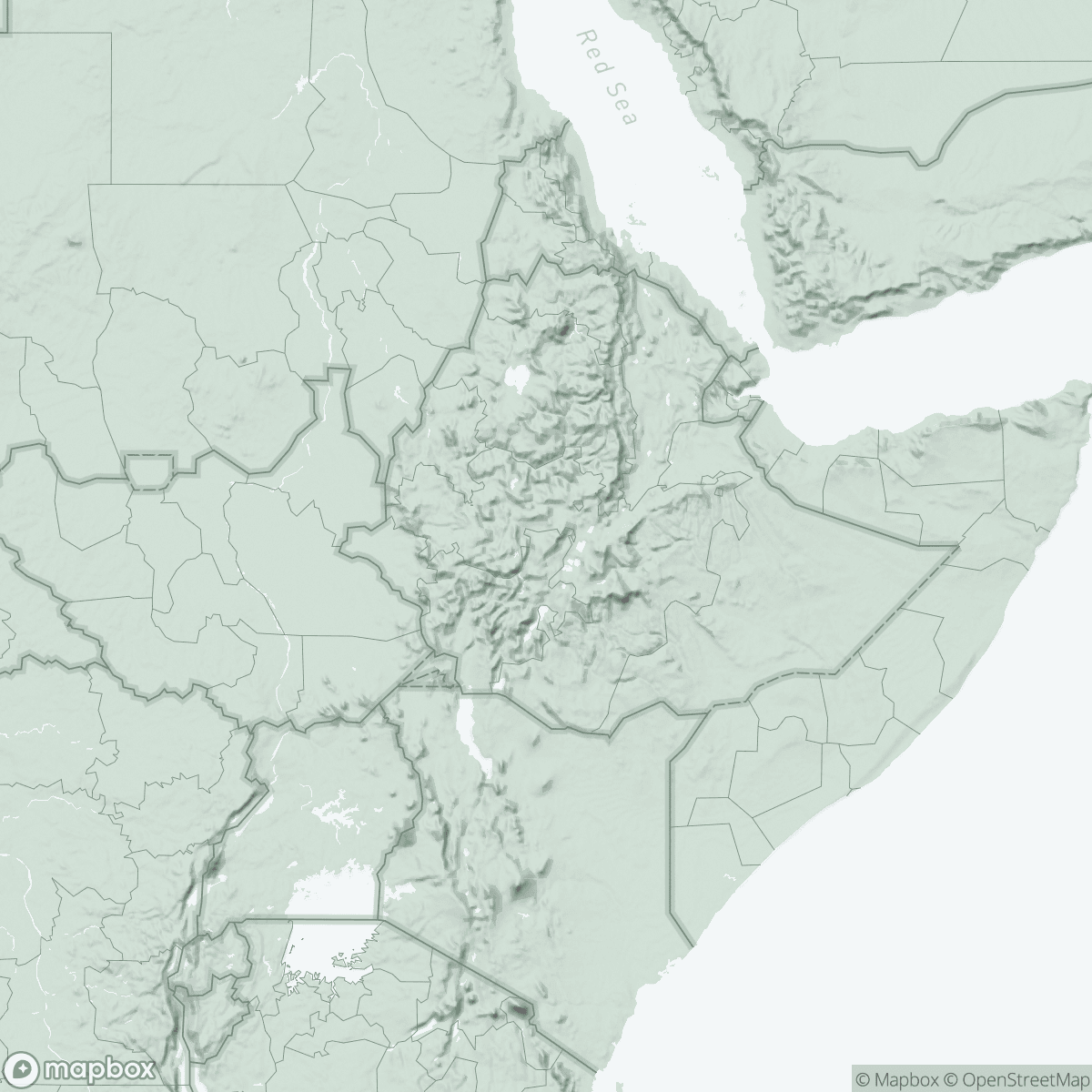

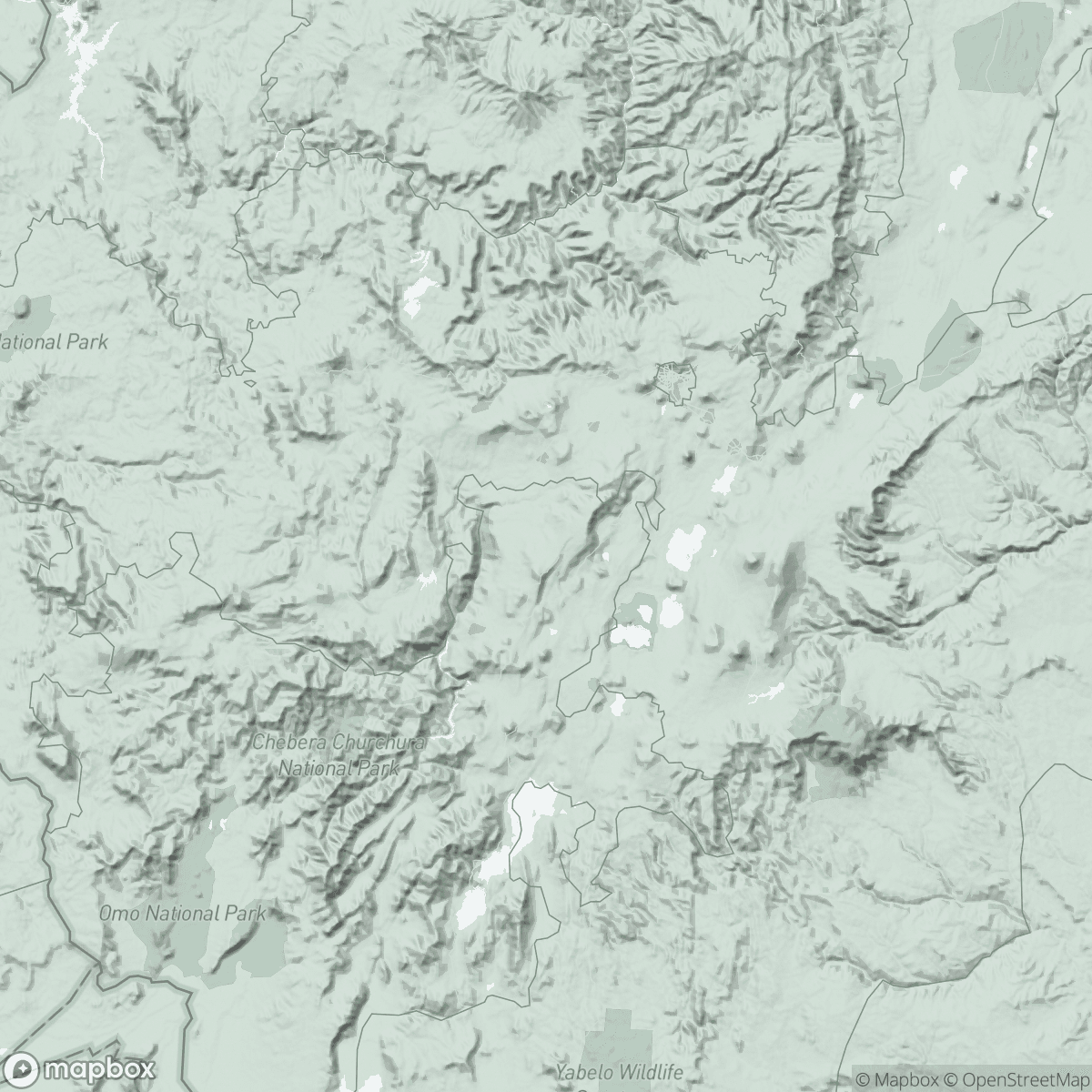

Since the end of January, MSF is sending mobile medical teams to provide patients in villages and towns north, east and south east of Shire with primary health care. We are also supporting some health facilities with medical supplies and just opened a base in the north-western town of Sheraro, from where we are supporting the town’s rural catchment area.

*Names have been changed