Hepatitis C care shortage leaves most Rohingya refugees uncured amid high prevalence in camps

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

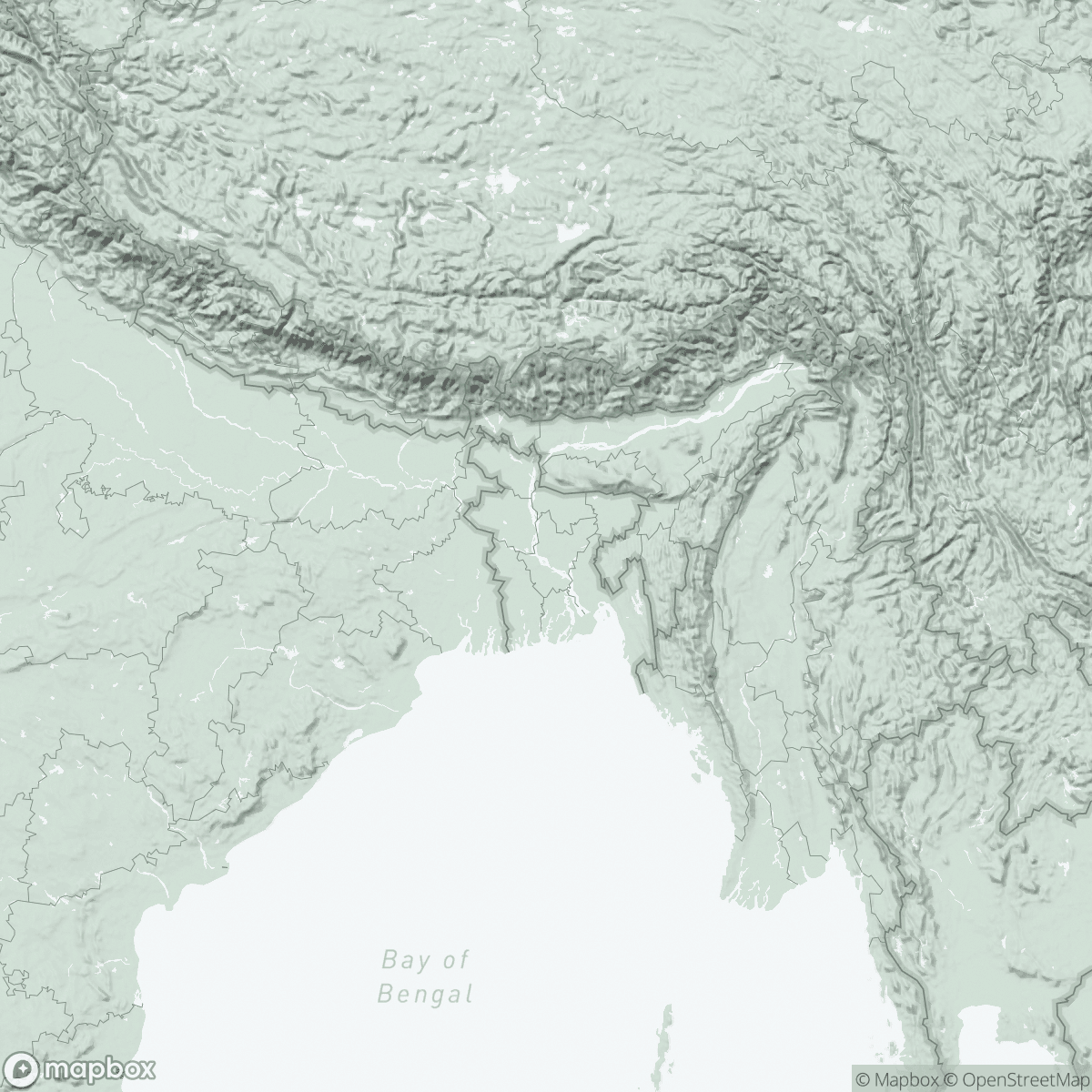

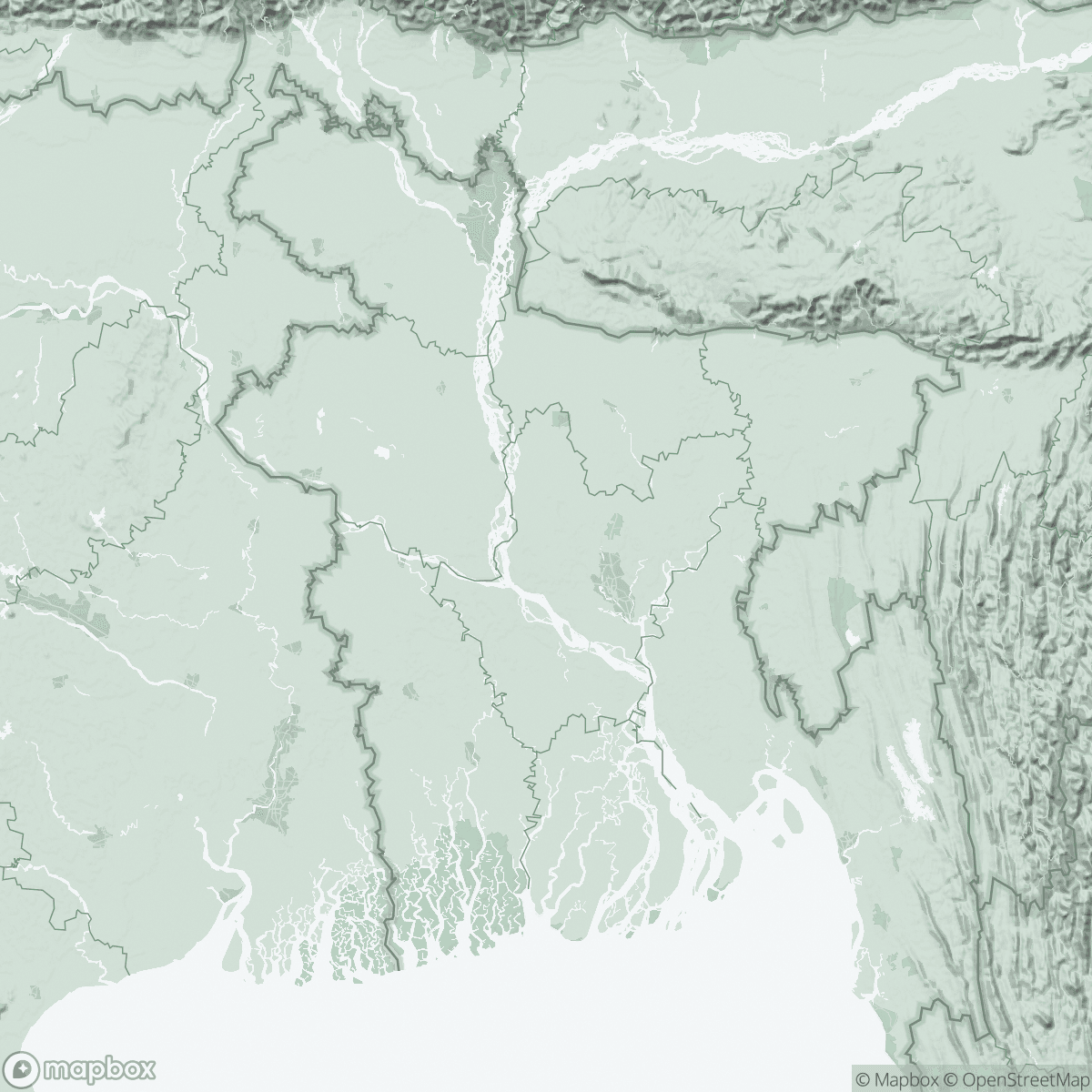

Nearly 20% of Rohingya refugees tested in the camps of Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, have an active hepatitis C infection. This is the finding of a recent study carried out by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and Epicentre, the epidemiology and medical research arm of MSF. This alarming figure highlights the consequences of decades of inadequate healthcare and difficult living conditions, characterised by violence, discrimination and insecurity.

Every day, hundreds of patients line up in a seemingly endless queue outside the MSF specialised clinic in Cox's Bazar in the hope of being cured. They have witnessed the devastation caused by hepatitis C, having lost family members here or when they were living in Myanmar."

explains Dr Wasim Firuz, deputy medical coordinator at MSF

For the past four years, he and his team have been able to treat only a tiny proportion of the Rohingya refugees affected by this infectious disease, which is often diagnosed in several members of the same family. This is the case of Mujibullah, whose wife and two sisters are infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV). His mother, who has now died from it, was worried that the virus would spread to the whole family; and about the cost of treatment.

A recent survey* carried out by MSF and Epicentre in the Cox's Bazar camps reveals that at least one in three Rohingya adults has been exposed to the virus and almost one in five has chronic active hepatitis C – amounting to an estimated 86,000 individuals. Since October 2020, MSF has seen more than 8,000 patients; that’s between 150 and 200 new patients every month, but even this number of consultations is not sufficient to meet the needs

In the five or six months before I started HCV treatment, I felt so bad that I couldn't even get to the market right next door to us. Every time I thought about the journey, I felt like I was going to collapse on the road, I was weak, tired and nauseous. I took the treatment for three months and felt better. The tiredness, loss of appetite and pain gradually disappeared.”

says Shamsul, who has been living in the camp since 2017

* Epicentre, MSF's epidemiology and research centre, carried out a survey of 680 households in seven camps between May and June 2023.

Effective treatment, limited access

Access to diagnosis and treatment remains inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries, as is the case in Bangladesh. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that hepatitis C had led to the deaths of 242,000 people worldwide, mainly from complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Since 2014, direct-acting antivirals have made it possible to treat hepatitis C effectively. MSF teams used these treatments to treat around 19,000 people in Cambodia between 2016 and 2021. After the emergence of the camps in Cox's Bazar, MSF decided to launch a simplified model for the treatment of hepatitis C in the Rohingya community in 2020, based on the one in Cambodia.

This model is based on the use of rapid diagnostic tests and a reduced number of follow-up visits and tests.This means that treatment initiation is faster and extremely effective.

From the outset, it was clear that demand for hepatitis C treatment was high in the camps, with very long queues. There was an urgent need to understand the burden of the disease by estimating the number of people requiring diagnosis and treatment.”

explains Dr Farah Hossain, MSF medical programs deputy manager

Although Bangladesh has a plan to combat viral hepatitis, the cost of diagnosis and treatment remains high. Each diagnostic test, for example, costs 20 US dollars and each person tested must be tested twice, with a total cost of 40 US dollars per person, which further increases the medical costs borne by patients.

In the Cox's Bazar camps, MSF clinics are the only places offering free treatment, so this is where hundreds of Rohingya go. They have been living in precarious conditions since 2017; and remain living in camps they cannot leave and where they are reliant on humanitarian aid as they are not allowed to work.

HCV treatment has only been available in the MSF hospital, which makes it difficult for people to access the medicines they need to be cured and have a chance of survival before it gets worse."

says Shamsul

Unfortunately, we cannot treat everyone because of limited resources. We treat people aged between 40 and 70. Younger people have a chance of self-remission and it usually take years for them to develop complications, while older people are more vulnerable.”

explains Dr Wasim

Massive need for treatment in the camps

Hepatitis C is blood-borne and is usually transmitted through unsterilised needles and unsafe medical practices. According to the study carried out by MSF and Epicentre, exposure to these practices could be the main risk factor in the specific and confined context of the camps.

Around 70 per cent of the people who took part in the MSF study reported having received therapeutic injections, either in the camps in Bangladesh or in Myanmar, often in medical establishments, from traditional healers or during childbirth carried out in the traditional way. Harsh living conditions in cramped and overcrowded camps, lack of access to healthcare, lack of legal status and reduced healthcare provision have made Rohingya refugees more vulnerable to infections, including hepatitis C.

After experiencing the symptoms of hepatitis C, I consulted a traditional healer to obtain herbal remedies. These remedies, made from vines and scales of plants, tasted very bitter. My wife, who also had hepatitis C, took them and felt better. Encouraged by her improvement, I started taking them. At first we felt some relief, but after a few days the symptoms returned, and my wife began to experience symptoms similar to mine."

says Shamsul

Hepatitis C has become a major concern for the whole community. Seeing people’s pain and frustration breaks my heart. As a member of this community, I share their struggles. I wish we could treat everyone, but we can't. The fear of hepatitis C remains, a constant reminder of the difficult choices we face.”

says Baduran, a community health worker with MSF

Breaking the chain of transmission

Enormous progress has been made in the treatment of hepatitis C in recent years, with success rates of up to 95 per cent, thanks to the new direct-acting antivirals. This rate is also being observed by

MSF teams in the Cox's Bazar camps. A massive HCV testing and treatment campaign needs to be implemented in all Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, which requires a rapid increase in access to testing and treatment.

At the same time, we need to break the chain of transmission through a large-scale prevention and health promotion campaign. A multi-partner initiative involving humanitarian and health players is needed to coordinate these efforts.”

says Dr Farah Hossain

Most people with HCV have no symptoms until the disease becomes serious, threatening their lives after many years of progression, leading to jaundice or liver cancer.

If HCV is detected and treated in time, it can be eliminated, thereby preserving the health of the liver. In the long term, the integration of hepatitis C treatment in all health centres is necessary to prevent new cases and break the transmission chain.”

continues Dr Farah Hossain

MSF is currently working with the Bangladesh Ministry of Health to draw up a national plan for the treatment of hepatitis C, based on the simplified treatment model implemented in the camps.

The simplified model of care, ready to be shared with all the medical actors in the camps, should facilitate the use of HCV tests and treatment. Health education campaigns are needed to address the lack of information on HCV prevention in the camps. Community activities to combat stigma and discrimination must also be implemented.

The announcement that the WHO, Save The Children and the International Organization for Migration is opening a programme to combat hepatitis C in the Cox's Bazar camps is an important step in the right direction.”

says Dr Farah Hossain

Many people in our camp share this silent struggle. Tests confirm the presence of the virus, but treatment remains costly. One thing is certain: there is a cure and many people have recovered. That's the hope I'm clinging to. The hope that one day the medicine my wife desperately needs will be available.”

says Jafar, a Rohingya refugee cared for by MSF

The Rohingya, a Muslim minority from Myanmar's Rakhine state, are among the world's most persecuted populations. For decades, they have suffered discrimination, violence and forced displacement. On August 25, 2017, a major campaign of targeted violence against the Rohingyas erupted in Myanmar, driving hundreds of thousands of them to escape to Bangladesh, to the Cox's Bazar camps, where they live in precarious conditions, entirely dependent on humanitarian aid.