“If seriously ill people can’t get to hospital, you can imagine the consequences”

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

“After several attempts, we finally entered the capital of Tigray, Mekele, with a first MSF team on 16 December, more than a month after the violence started. The city was quiet. There was electricity, but no basic supplies. The local hospital was running at 30 to 40 per cent, with very little medication. Most significantly, there were almost no patients, which is always a very bad sign. We evaluated the hospital, with the idea of referring patients there as soon as possible from Adigrat, 120 kilometres to the north.

We arrived in Adigrat, the second most populous city in Tigray, on 19 December. The situation was very tense, and its hospital was in a terrible condition. Most of the health staff had left, there were hardly any medicines and there was no food, no water and no money. Some patients who had been admitted with trauma injuries were malnourished.

We supplied the hospital with medicines and bought emergency food in the markets that were still open. Together with the remaining hospital staff, we cleaned the building and organised the collection of waste. Little by little we rehabilitated the hospital so that it could function as another referral centre.

If hospitals don’t function properly and can’t be accessed, then people die at home. And when the health system is broken, vaccinations, disease detection and nutritional programmes don’t function either.

Albert Viñas, Emergency coordinator, Tigray, Ethiopia

On 27 December we entered Adwa and Axum, two towns to the west of Adigrat, in central Tigray. There we found a similar situation: no electricity and no water. All the medicines had been stolen from Adwa general hospital and the hospital furniture and equipment were broken. Fortunately, the Don Bosco institution in Adwa had converted its clinic into an emergency hospital with a small operating theatre. In Axum, the 200-bed university hospital had not been attacked, but it was operating at only 10 per cent capacity.

On roads where the security situation remained uncertain, we trucked in food, medicines and oxygen to these hospitals and began to support the most essential medical departments, such as the operating theatres, maternity units and emergency rooms, and to refer critical cases.

Health centres looted and not functional

Beyond the hospitals, around 80 or 90 per cent of the health centres that we visited between Mekele and Axum were not functional, either due to a lack of staff or because they had suffered robberies. When the basic healthcare service does not exist, people can’t access or be referred to hospitals.

Before the crisis, two appendicitis operations were performed on any single day at Adigrat hospital. In the past two months, they haven’t done a single one. In every place, we saw patients who had struggled to get to hospital. One woman had been in labour for seven days without being able to give birth. Her life was saved because we were able to transport her to Mekele. I saw people arrive at hospital on bicycles carrying a patient from 30 kilometres away. And those were the ones who managed to get to hospital…

If women with complicated deliveries, seriously ill patients and people with appendicitis and trauma injuries can’t get to hospital, you can imagine the consequences. There are large numbers of people suffering, surely with fatal consequences. Adigrat hospital has a catchment area of more than one million people and the one in Axum has more than three million.

If these hospitals don’t function properly and can’t be accessed, then people die at home. And when the health system is broken, vaccinations, disease detection and nutritional programmes don’t function either. There have been no vaccinations in almost three months, so we fear there will be epidemics soon.

In recent weeks, our mobile medical teams have started visiting areas outside the main cities and we are reopening some health centres. We have seen some health staff returning to work. Only five people attended the first meeting we organised in Adwa hospital, but the second was attended by 15, and more than 40 people came to the third.

Fear, queues and lack of basic services

In this part of Tigray, there are no large settlements of displaced people – instead, most have taken refuge in the houses of relatives and friends, so many houses now have 20 or 25 people living there together. The impact of the violence is visible in the buildings and in the cars with bullet holes.

Especially at the beginning, we saw people locked in their homes and living in great fear. Everyone gave us pieces of paper with phone numbers written on them and asked us to convey messages to their families. People don’t even know if their relatives and loved ones are okay, because in many places there are still no telephones or telecommunications.

When we arrived in Adigrat, we saw queues of 500 people next to a water truck waiting to get 20 litres of water per family at most. The telephone line was restored in Adigrat just a few days ago. The situation is improving little by little, but as we moved westwards to new places, we found the same scenario: fewer services, less transport...

We are very concerned about what may be happening in rural areas. We still haven’t been able to go to many places, because access is still difficult, either because of insecurity or because it is hard to obtain authorisation. But we know, because community elders and traditional authorities have told us, that the situation in these places is very bad.

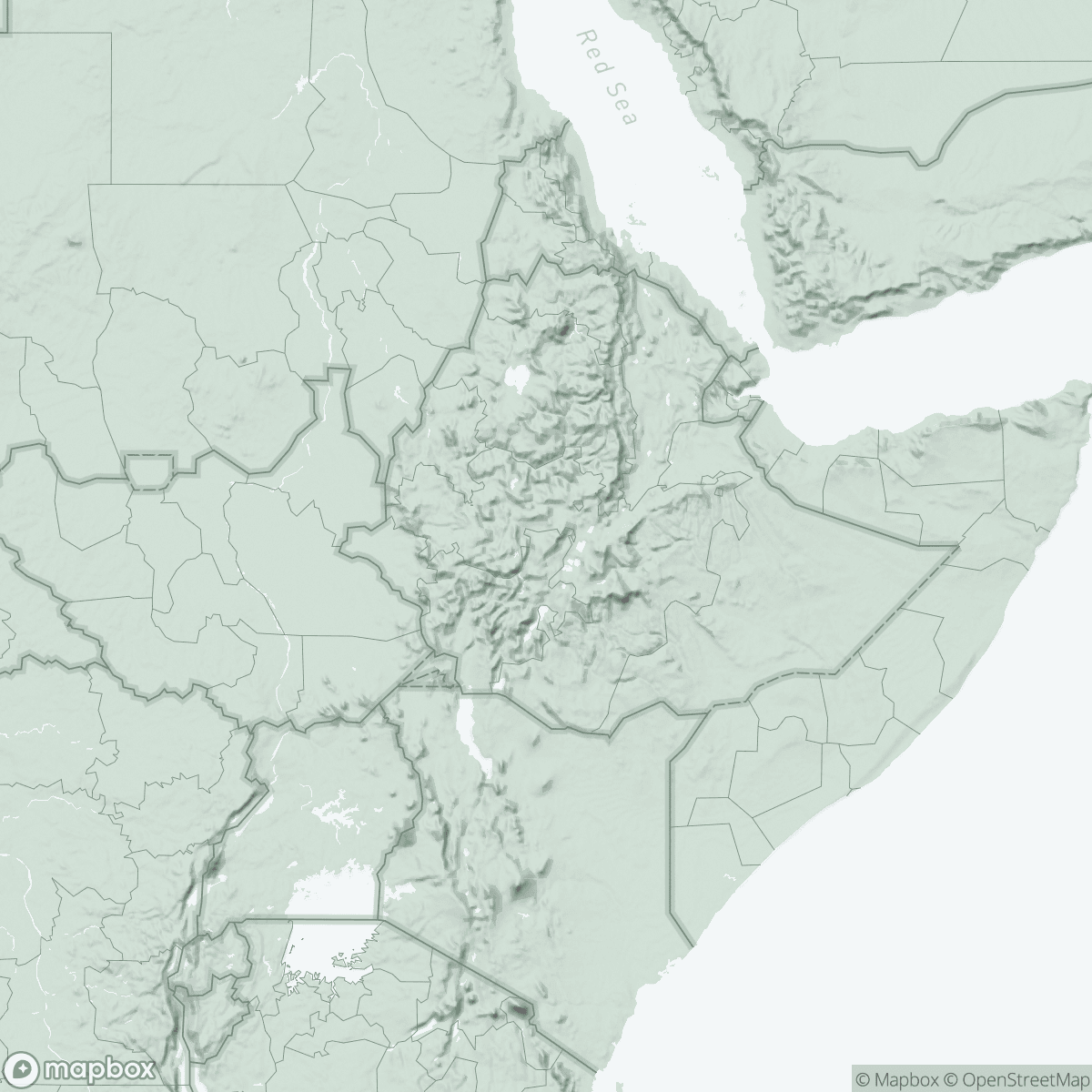

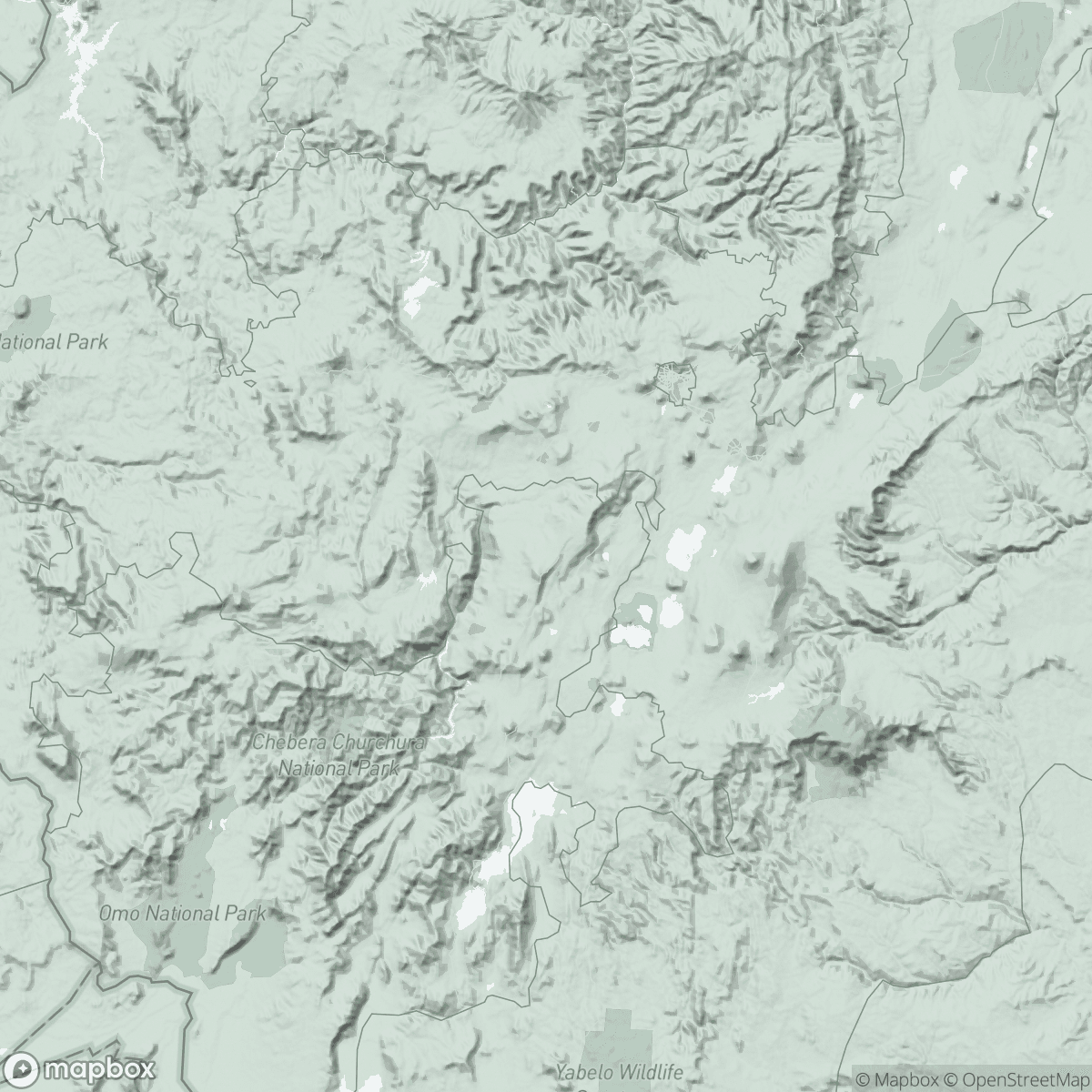

Large areas of Tigray have a very mountainous terrain, with winding roads that climb from 2,000 metres above sea level to 3,000 metres. Cities like Adwa and Axum are built on the fertile highlands, but large numbers of people live in the mountains and we have heard that there are people who have fled to these more remote areas because of the violence.

Logistical challenges, late response

The effort of our teams has been huge at all levels – medical, financial, logistical and human resources. It’s an incredible challenge without telephone or internet. At first there were no flights to Mekele and we had to move everything by road from the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, about 1,000 kilometres away. You couldn't make money transfers because the banks were all closed. Yet we managed to start our operations.

Now, almost three months after the start of the conflict, other organisations are beginning to appear, little by little, in some areas. I am struck by how difficult it has been – and continues to be – to access people in great need in such a densely populated area. Considering the means and capacity for analysis possessed by international organisations and the UN, the fact that this is happening is a failure of the humanitarian world.

We still don’t know the real impact of this crisis, but we have to keep working to find it out as soon as possible.”