ITALY-LIBYA AGREEMENT: Five years of EU-sponsored violence and abuse in Libya and the central Mediterranean

In 1 click, help us spread this information :

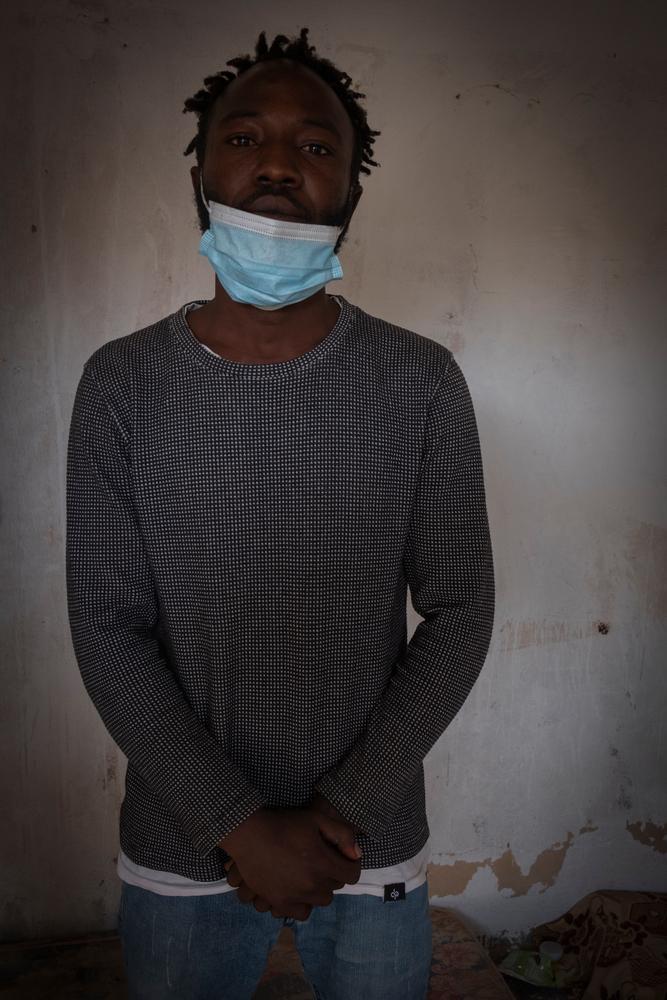

Nine hundred dollars meant the difference between imprisonment and freedom for 23-year-old Kouassi [not his real name], who fled his home in Côte d’Ivoire only to be sold to human traffickers in Libya. After being rescued from an unseaworthy boat drifting in the central Mediterranean by MSF’s search and rescue ship Geo Barents, Kouassi told the team on board that he had been detained in Libya for three months in 2020 after crossing the border from Algeria.

“They [the guards] put shackles on our ankles and wrists,” said Kouassi. “I have many scars on my ankles. I spent three months in shackles. They beat us – they hit us with wooden and metal sticks. I still have scars from cuts with knives on my back. It was a prison in the desert, a house that wasn’t finished to which we had been sold. We were around 10 in one room and there were several rooms. They removed everything we had on us. They asked for half a million CFA francs [US$900] from our parents for our release.”

Like Kouassi, thousands of women, children and men are trafficked, exploited, arbitrarily detained, tortured and have money extorted from them in Libya simply because they are migrants. On arrival in the country, many migrants are kidnapped and kept captive by militias or other armed groups or used by traffickers and smugglers as currency. Migrants living in cities are discriminated against, persecuted and face the constant threat of mass arrests and arbitrary incarceration.

“Catastrophic, that’s how I’d describe the current situation in Libya,” says Mustafa [not his real name], a migrant from Mali who has lived in Libya for several years. “A foreigner is like a blood diamond – they can be kidnapped to make money out of them. Money to be released and then maybe kidnapped again. Few migrants ended up dying in the prison, and when they did, they were simply thrown out as if they were animals. Their families don’t even know where they are buried. This is why people like me are suffering here. And Europe is giving tools to fuel this system of suffering.”

I was tortured and beaten. They [the guards] took burnt plastic and put it on my body.

Bashir, 17, from Somalia

Several international reports, as well as thousands of accounts by survivors, have documented the heinous treatment meted out to migrants and refugees in Libya. In November 2021, the UN fact-finding mission in Libya found these violations to be crimes against humanity.

Yet European governments have turned a blind eye to these crimes. The overwhelming evidence has not prevented them from making deals with the Libyan authorities to control migration to Europe.

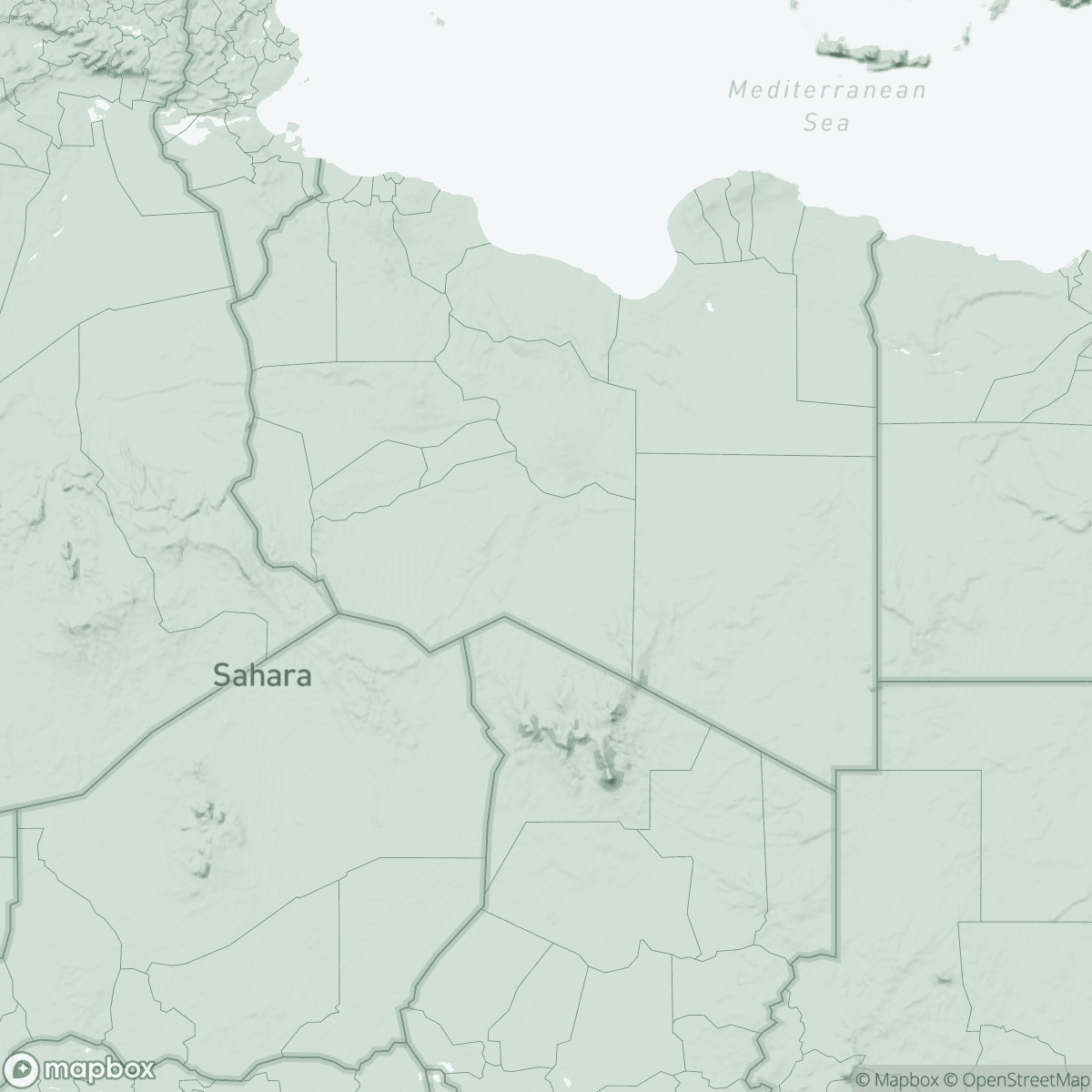

In February 2017, the Italian government signed an EU-sponsored agreement with the Libyan government: the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Migration1. Renewed in 2020 for a further three years, the MoU is part of a broader defensive strategy being pursued by European governments, based on a security approach against migrants. Rather than giving migrants protection, it seeks to keep them out.

Under this agreement, Italy and the EU have been helping the Libyan Coastguard to enhance their maritime surveillance capacity, providing them with financial support and technical assets. Since 2017, Italy has set aside €32.6 million for international missions to support the Libyan Coastguard, with €10.5 million allocated in 2021.

This help comes at the expense of migrants and refugees’ human rights, as virtually everyone intercepted at sea by the Libyan Coastguard ends up in a Libyan detention centre. The agreement between Italy and Libya supports the system of exploitation, extortion and abuse in which so many migrants find themselves trapped.

“I was tortured and beaten,” says Bashir, 17, from Somalia, who was held for a year in solitude and complete darkness in a cramped cell in an unofficial detention centre in Kufra. “I prayed to God to take my soul instead of being tortured. They [the guards] took burnt plastic and put it on my body. I was staying in a building; when you go inside, it’s a small room, you can’t even see, you have to be sitting. Alone in the room, with nothing. No windows. I stayed for one year. When I was released, I couldn’t walk on my feet the first day because I couldn’t open my knees. And I couldn’t see anything because I was in the dark for one year.”

In the absence of safe and legal routes out of Libya, for most migrants the only path to safety is crossing the Mediterranean Sea. Many survivors recount multiple attempts to cross what is considered the deadliest migration route in the world, which resulted in being detained in Libya and trapped in a cycle of violence, abuse, and extortion.

While the European governments ceded responsibility to Libya for overseeing rescue operations in a vast area of the Mediterranean Sea, rather than ensuring a proactive and dedicated state-led search and rescue capacity in the central Mediterranean Sea, an estimated 1,553 people died in the attempt to cross last year.

“People who cross the Mediterranean have no choice but to do so,” says Juan Matias Gil, MSF head of mission for search and rescue operations in the central Mediterranean. “European governments have the power to decide on migration policies, yet they have chosen deterrence strategies and border defense over respect for human rights and protecting people’s lives.”

“Rather than creating voluntary, legal and safe alternatives to crossing the Mediterranean Sea, the EU and Italy have struck a deal in which Libya serves as a place where migrants and asylum seekers are contained,” says Gil. “Meanwhile Europe looks away while in Libya a system of exploitation, extortion and abuse is funded and promoted by the EU and Italy. We urge the Italian government and EU institutions to end all direct and indirect political and material support for the system of returning migrants, refugees and asylum seekers to Libya and detaining them there.”

1The activities implemented under the MoU are funded through the Italian ‘Missions Decree’, the legal framework via which the Italian government and parliament authorise and fund international military commitments, and the EU programme ‘Support to integrated border and migration management in Libya’ (also known as IBM, or Integrated Border Management). 42 million euros financing the IBM come from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), a programme to support Libyan border management authorities, search and rescue activities at sea and on land, as well as law enforcement.