Hepatitis C Campaign in Rohingya Refugee Camps

Hepatitis C Campaign in Rohingya Refugee Camps

A Rising Concern

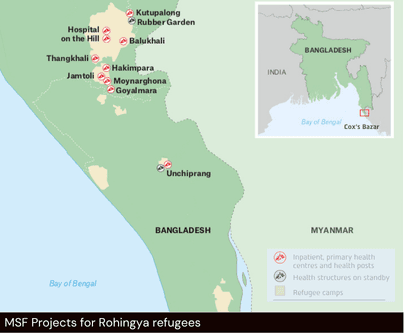

The Rohingya people, a stateless Muslim ethnic minority from Myanmar’s Rakhine State, have faced decades of discrimination, violence and displacement. Following mass violence in 2017, nearly one million fled to Bangladesh, joining existing refugees to form the world’s largest refugee settlement in Cox’s Bazar. Life in these camps is marked by insecurity, stress and limited access to services.

Within these fragile conditions, a rising concern has taken root: Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). This bloodborne infection can cause severe liver damage, scarring or cancer if left untreated. Yet for years, effective treatment was absent from both Bangladesh’s health system and humanitarian health packages, leaving most patients without care.

"Test and Treat" Campaign

In April 2025, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) launched a large-scale Hepatitis C campaign to screen and treat 30,000 patients within a year. The initiative uses two key approaches:

- Door-to-Door method: Reaching vulnerable individuals directly in their homes, especially those with limited mobility.

- Sentinel Site Screening: Conducting mass screenings at central locations to encourage participation and streamline operations.

To complement the medical response, MSF also sought to better understand the social determinants shaping the spread of HCV. Thus, an anthropological assessment was carried out between April and July 2025 by LuxOR and the Operational Centre Brussels of MSF, authored by Frida Romero Suarez. Understanding how people live with and respond to disease is essential for ensuring that public health campaigns are both effective and trusted.

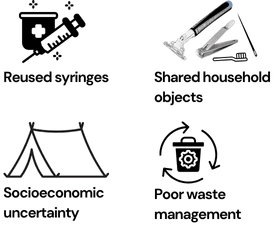

The assessment highlighted several key factors (more of which are included in full report) driving transmission and complicating care:

- Block doctors* are forced to use unsafe and shared injections

- Incorrect waste disposal exposing children to sharp objects

- Gender inequalities restricting women’s access to healthcare and information

- Broader insecurity and discrimination jeopardizing health care as a priority

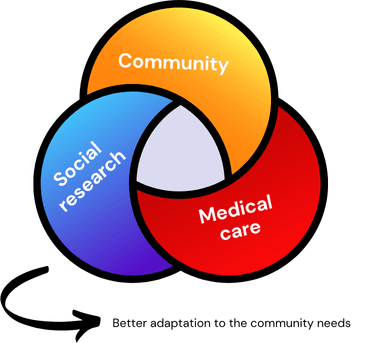

These insights show why Hepatitis C cannot be treated as a medical issue in isolation. Integrating social understanding with clinical care is vital to design effective, community-centred strategies for prevention and treatment in Cox’s Bazar.

*block doctors: informal, unlicensed male practitioners who provide basic biomedical care in refugee camps

Uncovering the Social Roots of the Disease

Cognitive biases regarding injections

Daily survival practices shape cultural practices that strongly influence how people seek and maintain health in the camps. One common example is the widespread use of injections - even for minor illnesses - because many believe they work faster.

Injections’ risks

However, this practice carries serious risks. Some patients who cannot afford new syringes may accept reused ones, while some providers continue to give unnecessary injections to meet community expectations and maintain trust.

Beyond injections, transmission risks of HCV extend into everyday life. Household objects such as razors, nail cutters, sewing needles and toothbrushes are frequently shared due to economic hardship and crowded living conditions.

Shared instruments' risks

Untraditional practices like umbilical cord cutting with bamboo sticks, abscess* draining with reused needles, and body piercings with shared instruments were also reported, alongside routine reuse of blades by barbers.

Stress, displacement and poverty

Poor waste disposal makes things worse. Used syringes and other sharp objects are often discarded in open spaces or mixed with regular trash, where children can easily come into contact with them.

These unsafe practices, compounded by stress, displacement and poverty, create what researchers described as a state of “bodily vulnerability” where treatment is often delayed until illness becomes severe.

Main causes of bodily vulnerability

Women's access to healthcare

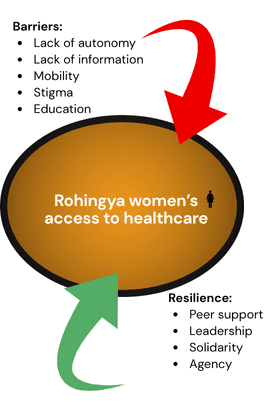

Anthropologists also found that gender inequality makes it much harder for women in the camps to get healthcare. Many women aren’t allowed to move freely and often need permission or a male relative to go to a clinic. Because of limited education and strict social rules, they also struggle to get accurate health information. Instead, they rely on male family members, who may not fully understand the issues.

Women's lack of autonomy

Healthcare decisions are usually made by husbands or mothers-in-law, reinforcing women’s lack of autonomy. In the crowded camp environment, fear of gossip or judgment - especially around relationships - adds more pressure. Without safe and private places to talk about sensitive health problems, some women suffer in silence, and in extreme cases, this can lead to self-harm.

Women's peer support

Yet within these constraints, women also demonstrate resilience and initiative. Peer solidarity and informal leadership networks create discreet channels for sharing information and offering support. These trusted spaces allow women to access care more safely and build confidence in the health system.

How gender inequalities shape health access

Bridging Medicine and Society

MSF Highlights

Combining medical care with social research has been key to improving the Hepatitis C campaign in Cox’s Bazar. By offering large-scale testing and treatment while also learning how people live and make health decisions, MSF can better adapt its services to the real needs of the community.

This holistic approach led MSF to make practical recommendations. These include training women’s groups in basic health education and working with block doctors to promote safe injection practices. MSF plans to continue building on this work—treating Hepatitis C as a basic right, making sure care is sensitive to gender issues, and keeping strong ties with the community.

Public support is still crucial. Raising awareness about the Rohingya’s health challenges helps secure funding and ensures fair access to care, paving the way for long-term improvements in humanitarian health.